The Llyn Brianne Water Scheme By Dafydd Dafis.

Chapters

The first great controversy in the heads of the Tywi Valley was caused by a proposal to appropriate land in order to plant conifers; the bone of contention in the second campaign was the drowning of the land in order to build a reservoir.

The background

Early in the 1960’s the local authorities in West Glamorgan had been searching for a location in which to build a reservoir to meet the needs of their population and their industries. There was a fierce opposition to the proposal for the Gwendraith Fach river which would have drowned the village of Porthyrhyd. The authorities then set about to try to examine another Gwendraith Fach site, some three miles from Porthyrhyd which would have split the village of Llangyndeyrn, submerging eight houses and a thousand acres of agricultural land. The opposition became even fiercer and a Defence Committee was formed to protect the property. The residents refused to allow the engineers on to their land to carry out the geological survey which was necessary before the construction of the dam could begin. When the engineers came anywhere near the village the church bell would ring to warn the watchmen, and the engineers would be faced with locked gates, entrances obstructed and a populace determined to protect the land against developers. Although the authorities obtained injunctions from local magistrates and although the actions of the villagers were illegal, the men and women of the Gwendraith Valley continued in their opposition. The authorities realised that the only way to gain possession of the land was by force, and in the face of such determined opposition, they withdrew from the scheme and turned their attention instead to the highland about four miles to the north of the village of Rhandirmwyn.

The exploratory work on drilling the rocks proved that the site was satisfactory. The West Glamorgan authorities then proceeded to establish one board which could speak with one voice and formed The West Glamorgan Water Board on October 1, 1966, and soon the Board went ahead to apply for planning permission, water licences and the Llyn Brianne Water Scheme Order. But before work could begin, there would need to be a Public Inquiry as a result of the strong and unexpected opposition which arose against the water scheme.

Unexpectedly? Well, yes, because after all this was merely a remote, rural neighbourhood with a very meagre population of mountain farmers, and only one inhabited property would be drowned. Nor was there any political advantage in opposing, since, unlike Treweryn, this was not a case of supplying water to an English city. This would be water for Wales, and there was no threat to a well-populated community. Accordingly, the political parties kept a low profile. Another important factor in favour of the Water Board was that most of the area which it was intended to drown belonged to the Forestry Commission, a total of 332 acres, including 212 acres of plantation; and although there would be substantial losses to the Commission in roads and bridges and in land and trees, no opposition was expected from that quarter. So it transpired, and the Board had the ready co-operation of the Commission at all times. Opposition was not expected from the local authorities in Carmarthenshire because they had been to the fore in trying to persuade the Water Board to build the reservoir in the upper reaches of the Tywi Valley.

So what of the conservationists, those strange and unpredictable ‘green’ people who went on and on about protecting the environment and preserving our wildlife? Back in the 60’s these were a handful of eccentric naturalists who were ignored by the majority of the population. And finally, what of the statutory authorities who ought to be to the fore in an attempt to safeguard an area like the upper Tywi Valley, with its nature reserve, both national and local, and an area of such beauty that there was a scheme afoot to establish the area which had the Llyn Brianne as its focal point as the fourth National Park in Wales. The organisation which dealt with these matters at that time were the Nature Conservancy (later the Nature Conservancy Council) and the National Parks Commission (later The Countryside Commission); both organisations are now united under the title of, ‘The Countryside Council for Wales’. Although both organisations made observations and suggestions to the Inquiry neither objected to the water scheme.

Preparing for Battle

But there was opposition, and it began very quickly and simply with Miss Jane Jones of Troedrhiw-rhyddwen called on the local schoolmaster to ask for his co-operation to oppose the scheme and to call a public meeting at Rhandirmwyn School. The schoolmaster agreed and promised to undertake the secretarial work. Three public meetings were called. To the second meeting, on September 8, 1965 Mr Iorwerth Watkins, clerk to the borough of Swansea, was invited along with Mr R. J. Lillycrap, the borough’s water engineer, to explain the scheme. This they did, slowly, carefully and simply as though they were speaking to someone with very limited intelligence. When questions were invited, the intellectual powers of their audience soon became evident to them and both returned to Swansea wiser men, fully realising that they had a fight on their hands.

The Defence Committee

A Defence Committee was formed after the public meeting on September 22, 1965, with Emlyn Jones, Llanddewi Brefi as chairman, and Dafydd Dafis, headmaster of Rhandirmwyn School as secretary. The Committee members were: Miss Jane Jones, Troedrhiw-rhyddwen, Mr and Mrs E Davies, Hafdre, Llanwrtyd, Mr and Mrs L Hurley, Crickhowell, Dr Jerry James, Messrs. W. Jones, Troedrhiw-rhyddwen, R. Davies, Hafdre, W. Jones, Ystradffin, E.T. James, Bwlchyffin, J. Jones, Nantllwyd, D. Jones, Nantymaen, J. Jones, Maesglas, T. M. Proctor, Economic Forrest Group, W. M. Davis, Aberystwyth, H. M. Lloyd, Carmarthen, Eifion Davies, Carmarthen and I. Emlyn Thomas, Carmarthen. They proceeded to call for assistance in our fight against a powerful body which had sufficient resources and taxpayers’ money to mount a campaign which could be long and costly. An appeal was printed for circulation among the residents and friends of the district and Roger Davies, Hafdre, was elected Treasurer. We had the service of Alan Coulthard as Counsel to represent us at the Inquiry, instructed by Messrs. Walker Jones and Gardiner, solicitors from Swansea. It became obvious from the sum raised by the appeal that we could not afford to let the case proceed for more than ten days and that we would not have financial resources to enable us to call upon experts in the water and fishery industries to testify on our behalf. So the stage was set for the second campaign to defend the upper reaches of the Tywi valley against the developers and despoilers.

The Public Inquiry

The Public Inquiry opened at the Castle Hotel, Llandovery on December 13, 1966, conducted by A.S.R. Mutch, a water engineer! It continued on December 14, 15 and 16 and again on December 28, 29 and 30, 1966. There was then more than a month’s respite until it re-started on February 7, 8 and 9, 1967.

The Llŷn Brianne Water Scheme Order, 1966

The water scheme being considered comprised the following: a reservoir with a dam of about 300 feet high across the River Tywi about two miles north of the confluence of the Tywi and the Doethie; three fish traps, one across the Tywi below the dam to trap the fish on their way upstream, another across the Tywi and one across the Camddwr river in the uppermost parts of the reservoir in these valleys in order to trap young fish on their way down stream; the improvement of the main road from Llandovery and through Rhandirmwyn as far as the dam; to improve the road leading from Gallt-y-berau along the Doethie valley to Troedrhiw-rhyddwen and onwards over Penrhiwbie to Henfaes and Dalarwen by widening and levelling it and building a new bridge over the River Doethie. (Such was the opposition to this clause that it was withdrawn in its entirety from the Order at the beginning of the enquiry); although we lost the campaign we did gain the occasional victory and to restrict the damage done to the Tywi and Camddwr and to prevent it from spreading to the valleys of the Doethie and Pysgotwr rivers was a very important victory. The water in the reservoir would be utilised to regulate the Tywi so that the river itself would carry the water, rather than pipes, as far as Nantgaredig, (near Carmarthen) some forty miles down river, and from there it would be extracted from the river and pumped to the Lliw Isaf reservoir near Felindre, Swansea. Finally the water in the reservoir would be pumped to waterworks for treatment and purification before being distributed to the customers. The stones for the construction of the dam were hewn from the rocks nearby and from the rocks which were excavated in order to build an overflow alongside the dam. The overflow area was needed in order to release the surplus water. In addition to the masonry, clay would be needed for the nucleus of the dam wall and the intention was to dig that out of the Maesglas farmland on the road between Soar-y-Mynydd (chapel) and the Abergwesyn/Tregaron road. The dam would stand a little way downstream from the point where ‘Nant Brianne’ Nant-y-Bryniau (correct name) – (The Stream of the Hills) according to local farmers, meets the Tywi.

When full, the reservoir would hold 13,400 million gallons of water, enabling the Water Board to extract 86,000.000 gallons of water a day. The surface area of the water would be 518 acres and its highest point 905 feet above sea level. Other parts of the scheme would consist of new roads around the reservoir and a new bridge across the Tywi at the furthest point of the reservoir.

The Opponents

Such was the outline of the scheme. If successful, what would it entail to those who farmed the land and to others with a special interest in the area which was under threat? The protests were based mainly on the loss of agricultural land and the effect which the scheme would have on the ecology of the area. The list of organisations and individuals who opposed the Llyn Brianne Scheme at the Inquiry reflects the anxiety which was felt. This is the order in which they appeared, with the names of the witnesses:

The Tywi Valley Defence Committee – Dafydd Dafis.

The Council for the Preservation of Rural Wales – Simon Meade.

The Youth Hostels Association – Eric Bartlett.

The Ramblers’ Association – Eric Bartlett.

The Cyclists’ Touring Club – John Hurt.

The Brecknock Naturalists Trust – Mrs. I. M. Vaughan.

The Botanical Society of the British Isles – Mrs I. M. Vaughan.

The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds – David Lea.

West Wales Naturalists’ Trust – Professor P. F. Wareing.

Ms. Louise Hurley, Crickhowell.

Mrs. Yolande Hurley, Crickhowell.

Miss Jane Jones, Troedrhiw-rhyddwen.

Mrs E Lewis, Bwlchnewydd.

Canon H. Montefiore, Cambridge.

C. R. Davies, Hafdre.

E. T. James, Bwlchyffin.

W. Jones, Ystradffin.

I. T. Williams, Galltyberau.

Mrs S. Jones and her sons, Nantllwyd.

J. B. Sankey-Barker, Crickhowell.

Jan Zahorec, Felindre.

D. D. Jones, Felindre.

To the farmers, the scheme entailed the loss of agricultural land which would disappear beneath water, roads, car parks and buildings; some land was saved by the withdrawal by the developers of the plan for the road along the Doethie Valley, in the face of the fierce opposition to this aspect of the scheme. The development would also have an effect on the fish in the rivers and consequently upon those who hold fishing rights. Although the Defence Committee strongly criticised the intention to trap migratory fish below the reservoir and to transport them by lorry to places higher than the traps at the uppermost end of the reservoir where they would be released into the Camddwr River and into part of the Tywi where they had not been before – none of us anticipated the disastrous effect which the scheme would have on the fish in the River Tywi and its tributaries. The Llyn Brianne developers claimed before the Inquiry that fishing would improve once the scheme had been completed; the Water Board would be able to release water from the reservoir when the level of the river was low and thus create an artificial stream which would attract the salmon and sewin up river, with great benefits to the fishermen. This fable was swallowed hook, line and sinker by the fishermen, and not a single fishing club was seen to oppose the scheme during the Inquiry.

The Defence Committee and the committees which were concerned with nature conservation, such as the ornithologists, the botanists and the naturalists opposed the Water Scheme Order because of the great loss of important natural environments which housed a variety of flora and fauna, some of which were scarce on a national scale. The reservoir would be built in the middle of an area designated by the Nature Conservancy in 1954 as a Site of Special Scientific Interest. Moreover, within some three miles of the reservoir there were national and local nature reserves, seven of them in all: the Allt Rhyd-y-groes National Nature Reserve, of 153 acres, on the banks of the Doethie and Pysgotwr rivers; the Nant Irfon National Nature Reserve, 216 acres including 45 acres of Quercus petraea, the Sessile oak; the 1200 acres of the Gwenffrwd and Dinas Reserves, the property of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, and including a variety of environments – pastures, oak woods, farmland, streams and moors; the Allt yr Hwch Nature Reserve, comprising 50 acres under the care of the Carmarthenshire Education Committee, and established with the co-operation of the Forestry Commission; and finally three reserves set up by the West Wales Naturalists’ Trust (now the Dyfed Wildlife Trust), namely Goyallt, the oak wood on the hill behind Rhandirmwyn School; Nant Melin, a mixed forest of oak and ash with a small bog of botanic interest on the bank of the Melin in the Gwenffrwd valley, and Llyn y Gwaith, the lake of the old lead mine at Nantybai. It would be difficult to find any other area in Britain which has so many nature reserves encompassed in such a small area.

Magnificent oak forests such as Allt yr Hwch on the Dalarwen land and Coed-cae-gwartheg on the Trawsnant land would be destroyed. The significance of forests such as these is not confined to their own boundaries; rather they contribute to the surrounding areas by housing a variety of wildlife and influencing the environmental factors in the neighbouring areas. Although they provide a home for varieties of plants and rare or uncommon animals, they should not be preserved merely for these reasons but because they are excellent examples of a particular type of forest and of an environment. Allt yr Hwch was used as a nature reserve by the schools of the county; near to the old road which ran through the woodland a cedar cabin was built on a height of about 1000 feet, with laboratory facilities where pupils could study oak wood ecology at an elementary level or at sixth-form level. The woodland was a prime example of a high altitude sessile oak wood. It stood on steep and shady slopes where the oaks grew to 1200 feet above sea level. To see oak trees growing at this level is an uncommon occurrence in Britain and is confined to Dartmoor, the Lake District and some of the mid-Wales valleys. On the ground were the ordinary plants you would normally expect; the wood anemone, the lesser celandine, the common dog violet, the slender St. John’s Wort. The great stitchwort, herb Robert, the wood sorrel, the rose-bay willow herb, the enchanter’s nightshade, dog’s mercy, primrose, yellow pimpernel, fox-glove, ground ivy, wood sage, the bluebell, and numerous varieties of hay and rushes. Less common plants which grew in the woodland or near it were: the upright vetch, the wood horse-tail, the ivy-leaved bellflower, the mountain pansy, the sawwort, purging flax, woodruff, and the burnet saxifrage. Over a large area of Allt yr Hwch ground there was common cow-wheat, the bilberry and heather, sure indicators of the acidity of the soil in these places. Among the ordinary trees you would expect to find in these parts there were more unusual examples in this wood, such as the aspen, with its leaves quivering in the slightest breeze, so that the name of ‘Tafod Merched’ (Ladies Tongue) has also been ascribed to the tree. In addition, there was the small leaved lime, two of which were felled along with oaks and birches, ash and rowan-tree the broad-leaved elm, the alder and willow, beech and holly, the hawthorn and blackthorn and hazel. They were all felled within the Llyn Brianne basin up to a height of 915 feet before drowning the valley.

The Birds

The oak trees provided a home for many common resident birds such as the buzzard, the woodcock, the cuckoo, tawny owl, green woodpecker and great spotted woodpecker, the crow, jackdaw, jay, the great tit, the blue tit, the coal tit, marsh tit and long tailed tit, the nuthatch, treecreeper, wren, pied wagtail and thrush, the blackbird, robin, hedge-sparrow, starling, chaffinch and wood-pigeon. They had found shelter and nesting places in the trees. Spring saw the arrival of the migratory birds, such as the pied flycatcher, redstart, garden warbler, blackcap, chiff-chaff and wood warbler. Around the rivers and streams could be found the dipper, the common sandpiper and the wagtail. Peter Hope Jones noted the crossbill, greenfinch and black grouse in the Allt yr Hwch reserve while undertaking research into the latter bird.

The oak woods of the reserve and Coed-cae-gwartheg formed a nesting-place for the kite from time to time since the beginning of the century, when its numbers had decreased disastrously to about half a dozen pairs. When the guns of the keepers and the landowners’ poison had completely swept this magnificent bird of prey from the skies above England and Scotland, it found a sanctuary from its persecutors here in the upper reaches of the Tywi Valley; ‘it was here and here only that were seen the pitiful remnants of this bird which had been a common scavenger on the streets of London in the time of Shakespeare and of Samuel Pepys’. Here the first steps were taken to try to safeguard the bird, measures which proved successful despite the slow growth in the kite population and disappointments in some years. Thanks to the watchfulness of the farmers and the perseverance of the conservationists over a long period of time, the red kite (or Boda’r Wennol as it is called locally) as preserved only just in time and its future assured. The dozen or so birds at the turn of the century grew to the present population. (375 in August 1992). In an age which suffered so many losses in both animals and plant life and their environments, it is pleasing to be able to note success in this particular case.

- The background

- Preparing for Battle

- The Defence Committee

- The Public Inquiry

- The Llŷn Brianne Water Scheme Order, 1966

- The Opponents

- The Birds

- The Gorges

- Notes

The first great controversy in the heads of the Tywi Valley was caused by a proposal to appropriate land in order to plant conifers; the bone of contention in the second campaign was the drowning of the land in order to build a reservoir.

The background

Early in the 1960’s the local authorities in West Glamorgan had been searching for a location in which to build a reservoir to meet the needs of their population and their industries. There was a fierce opposition to the proposal for the Gwendraith Fach river which would have drowned the village of Porthyrhyd. The authorities then set about to try to examine another Gwendraith Fach site, some three miles from Porthyrhyd which would have split the village of Llangyndeyrn, submerging eight houses and a thousand acres of agricultural land. The opposition became even fiercer and a Defence Committee was formed to protect the property. The residents refused to allow the engineers on to their land to carry out the geological survey which was necessary before the construction of the dam could begin. When the engineers came anywhere near the village the church bell would ring to warn the watchmen, and the engineers would be faced with locked gates, entrances obstructed and a populace determined to protect the land against developers. Although the authorities obtained injunctions from local magistrates and although the actions of the villagers were illegal, the men and women of the Gwendraith Valley continued in their opposition. The authorities realised that the only way to gain possession of the land was by force, and in the face of such determined opposition, they withdrew from the scheme and turned their attention instead to the highland about four miles to the north of the village of Rhandirmwyn.

The exploratory work on drilling the rocks proved that the site was satisfactory. The West Glamorgan authorities then proceeded to establish one board which could speak with one voice and formed The West Glamorgan Water Board on October 1, 1966, and soon the Board went ahead to apply for planning permission, water licences and the Llyn Brianne Water Scheme Order. But before work could begin, there would need to be a Public Inquiry as a result of the strong and unexpected opposition which arose against the water scheme.

Unexpectedly? Well, yes, because after all this was merely a remote, rural neighbourhood with a very meagre population of mountain farmers, and only one inhabited property would be drowned. Nor was there any political advantage in opposing, since, unlike Treweryn, this was not a case of supplying water to an English city. This would be water for Wales, and there was no threat to a well-populated community. Accordingly, the political parties kept a low profile. Another important factor in favour of the Water Board was that most of the area which it was intended to drown belonged to the Forestry Commission, a total of 332 acres, including 212 acres of plantation; and although there would be substantial losses to the Commission in roads and bridges and in land and trees, no opposition was expected from that quarter. So it transpired, and the Board had the ready co-operation of the Commission at all times. Opposition was not expected from the local authorities in Carmarthenshire because they had been to the fore in trying to persuade the Water Board to build the reservoir in the upper reaches of the Tywi Valley.

So what of the conservationists, those strange and unpredictable ‘green’ people who went on and on about protecting the environment and preserving our wildlife? Back in the 60’s these were a handful of eccentric naturalists who were ignored by the majority of the population. And finally, what of the statutory authorities who ought to be to the fore in an attempt to safeguard an area like the upper Tywi Valley, with its nature reserve, both national and local, and an area of such beauty that there was a scheme afoot to establish the area which had the Llyn Brianne as its focal point as the fourth National Park in Wales. The organisation which dealt with these matters at that time were the Nature Conservancy (later the Nature Conservancy Council) and the National Parks Commission (later The Countryside Commission); both organisations are now united under the title of, ‘The Countryside Council for Wales’. Although both organisations made observations and suggestions to the Inquiry neither objected to the water scheme.

Preparing for Battle

But there was opposition, and it began very quickly and simply with Miss Jane Jones of Troedrhiw-rhyddwen called on the local schoolmaster to ask for his co-operation to oppose the scheme and to call a public meeting at Rhandirmwyn School. The schoolmaster agreed and promised to undertake the secretarial work. Three public meetings were called. To the second meeting, on September 8, 1965 Mr Iorwerth Watkins, clerk to the borough of Swansea, was invited along with Mr R. J. Lillycrap, the borough’s water engineer, to explain the scheme. This they did, slowly, carefully and simply as though they were speaking to someone with very limited intelligence. When questions were invited, the intellectual powers of their audience soon became evident to them and both returned to Swansea wiser men, fully realising that they had a fight on their hands.

The Defence Committee

A Defence Committee was formed after the public meeting on September 22, 1965, with Emlyn Jones, Llanddewi Brefi as chairman, and Dafydd Dafis, headmaster of Rhandirmwyn School as secretary. The Committee members were: Miss Jane Jones, Troedrhiw-rhyddwen, Mr and Mrs E Davies, Hafdre, Llanwrtyd, Mr and Mrs L Hurley, Crickhowell, Dr Jerry James, Messrs. W. Jones, Troedrhiw-rhyddwen, R. Davies, Hafdre, W. Jones, Ystradffin, E.T. James, Bwlchyffin, J. Jones, Nantllwyd, D. Jones, Nantymaen, J. Jones, Maesglas, T. M. Proctor, Economic Forrest Group, W. M. Davis, Aberystwyth, H. M. Lloyd, Carmarthen, Eifion Davies, Carmarthen and I. Emlyn Thomas, Carmarthen. They proceeded to call for assistance in our fight against a powerful body which had sufficient resources and taxpayers’ money to mount a campaign which could be long and costly. An appeal was printed for circulation among the residents and friends of the district and Roger Davies, Hafdre, was elected Treasurer. We had the service of Alan Coulthard as Counsel to represent us at the Inquiry, instructed by Messrs. Walker Jones and Gardiner, solicitors from Swansea. It became obvious from the sum raised by the appeal that we could not afford to let the case proceed for more than ten days and that we would not have financial resources to enable us to call upon experts in the water and fishery industries to testify on our behalf. So the stage was set for the second campaign to defend the upper reaches of the Tywi valley against the developers and despoilers.

The Public Inquiry

The Public Inquiry opened at the Castle Hotel, Llandovery on December 13, 1966, conducted by A.S.R. Mutch, a water engineer! It continued on December 14, 15 and 16 and again on December 28, 29 and 30, 1966. There was then more than a month’s respite until it re-started on February 7, 8 and 9, 1967.

The Llŷn Brianne Water Scheme Order, 1966

The water scheme being considered comprised the following: a reservoir with a dam of about 300 feet high across the River Tywi about two miles north of the confluence of the Tywi and the Doethie; three fish traps, one across the Tywi below the dam to trap the fish on their way upstream, another across the Tywi and one across the Camddwr river in the uppermost parts of the reservoir in these valleys in order to trap young fish on their way down stream; the improvement of the main road from Llandovery and through Rhandirmwyn as far as the dam; to improve the road leading from Gallt-y-berau along the Doethie valley to Troedrhiw-rhyddwen and onwards over Penrhiwbie to Henfaes and Dalarwen by widening and levelling it and building a new bridge over the River Doethie. (Such was the opposition to this clause that it was withdrawn in its entirety from the Order at the beginning of the enquiry); although we lost the campaign we did gain the occasional victory and to restrict the damage done to the Tywi and Camddwr and to prevent it from spreading to the valleys of the Doethie and Pysgotwr rivers was a very important victory. The water in the reservoir would be utilised to regulate the Tywi so that the river itself would carry the water, rather than pipes, as far as Nantgaredig, (near Carmarthen) some forty miles down river, and from there it would be extracted from the river and pumped to the Lliw Isaf reservoir near Felindre, Swansea. Finally the water in the reservoir would be pumped to waterworks for treatment and purification before being distributed to the customers. The stones for the construction of the dam were hewn from the rocks nearby and from the rocks which were excavated in order to build an overflow alongside the dam. The overflow area was needed in order to release the surplus water. In addition to the masonry, clay would be needed for the nucleus of the dam wall and the intention was to dig that out of the Maesglas farmland on the road between Soar-y-Mynydd (chapel) and the Abergwesyn/Tregaron road. The dam would stand a little way downstream from the point where ‘Nant Brianne’ Nant-y-Bryniau (correct name) – (The Stream of the Hills) according to local farmers, meets the Tywi.

When full, the reservoir would hold 13,400 million gallons of water, enabling the Water Board to extract 86,000.000 gallons of water a day. The surface area of the water would be 518 acres and its highest point 905 feet above sea level. Other parts of the scheme would consist of new roads around the reservoir and a new bridge across the Tywi at the furthest point of the reservoir.

The Opponents

Such was the outline of the scheme. If successful, what would it entail to those who farmed the land and to others with a special interest in the area which was under threat? The protests were based mainly on the loss of agricultural land and the effect which the scheme would have on the ecology of the area. The list of organisations and individuals who opposed the Llyn Brianne Scheme at the Inquiry reflects the anxiety which was felt. This is the order in which they appeared, with the names of the witnesses:

The Tywi Valley Defence Committee – Dafydd Dafis.

The Council for the Preservation of Rural Wales – Simon Meade.

The Youth Hostels Association – Eric Bartlett.

The Ramblers’ Association – Eric Bartlett.

The Cyclists’ Touring Club – John Hurt.

The Brecknock Naturalists Trust – Mrs. I. M. Vaughan.

The Botanical Society of the British Isles – Mrs I. M. Vaughan.

The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds – David Lea.

West Wales Naturalists’ Trust – Professor P. F. Wareing.

Ms. Louise Hurley, Crickhowell.

Mrs. Yolande Hurley, Crickhowell.

Miss Jane Jones, Troedrhiw-rhyddwen.

Mrs E Lewis, Bwlchnewydd.

Canon H. Montefiore, Cambridge.

C. R. Davies, Hafdre.

E. T. James, Bwlchyffin.

W. Jones, Ystradffin.

I. T. Williams, Galltyberau.

Mrs S. Jones and her sons, Nantllwyd.

J. B. Sankey-Barker, Crickhowell.

Jan Zahorec, Felindre.

D. D. Jones, Felindre.

To the farmers, the scheme entailed the loss of agricultural land which would disappear beneath water, roads, car parks and buildings; some land was saved by the withdrawal by the developers of the plan for the road along the Doethie Valley, in the face of the fierce opposition to this aspect of the scheme. The development would also have an effect on the fish in the rivers and consequently upon those who hold fishing rights. Although the Defence Committee strongly criticised the intention to trap migratory fish below the reservoir and to transport them by lorry to places higher than the traps at the uppermost end of the reservoir where they would be released into the Camddwr River and into part of the Tywi where they had not been before – none of us anticipated the disastrous effect which the scheme would have on the fish in the River Tywi and its tributaries. The Llyn Brianne developers claimed before the Inquiry that fishing would improve once the scheme had been completed; the Water Board would be able to release water from the reservoir when the level of the river was low and thus create an artificial stream which would attract the salmon and sewin up river, with great benefits to the fishermen. This fable was swallowed hook, line and sinker by the fishermen, and not a single fishing club was seen to oppose the scheme during the Inquiry.

The Defence Committee and the committees which were concerned with nature conservation, such as the ornithologists, the botanists and the naturalists opposed the Water Scheme Order because of the great loss of important natural environments which housed a variety of flora and fauna, some of which were scarce on a national scale. The reservoir would be built in the middle of an area designated by the Nature Conservancy in 1954 as a Site of Special Scientific Interest. Moreover, within some three miles of the reservoir there were national and local nature reserves, seven of them in all: the Allt Rhyd-y-groes National Nature Reserve, of 153 acres, on the banks of the Doethie and Pysgotwr rivers; the Nant Irfon National Nature Reserve, 216 acres including 45 acres of Quercus petraea, the Sessile oak; the 1200 acres of the Gwenffrwd and Dinas Reserves, the property of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, and including a variety of environments – pastures, oak woods, farmland, streams and moors; the Allt yr Hwch Nature Reserve, comprising 50 acres under the care of the Carmarthenshire Education Committee, and established with the co-operation of the Forestry Commission; and finally three reserves set up by the West Wales Naturalists’ Trust (now the Dyfed Wildlife Trust), namely Goyallt, the oak wood on the hill behind Rhandirmwyn School; Nant Melin, a mixed forest of oak and ash with a small bog of botanic interest on the bank of the Melin in the Gwenffrwd valley, and Llyn y Gwaith, the lake of the old lead mine at Nantybai. It would be difficult to find any other area in Britain which has so many nature reserves encompassed in such a small area.

Magnificent oak forests such as Allt yr Hwch on the Dalarwen land and Coed-cae-gwartheg on the Trawsnant land would be destroyed. The significance of forests such as these is not confined to their own boundaries; rather they contribute to the surrounding areas by housing a variety of wildlife and influencing the environmental factors in the neighbouring areas. Although they provide a home for varieties of plants and rare or uncommon animals, they should not be preserved merely for these reasons but because they are excellent examples of a particular type of forest and of an environment. Allt yr Hwch was used as a nature reserve by the schools of the county; near to the old road which ran through the woodland a cedar cabin was built on a height of about 1000 feet, with laboratory facilities where pupils could study oak wood ecology at an elementary level or at sixth-form level. The woodland was a prime example of a high altitude sessile oak wood. It stood on steep and shady slopes where the oaks grew to 1200 feet above sea level. To see oak trees growing at this level is an uncommon occurrence in Britain and is confined to Dartmoor, the Lake District and some of the mid-Wales valleys. On the ground were the ordinary plants you would normally expect; the wood anemone, the lesser celandine, the common dog violet, the slender St. John’s Wort. The great stitchwort, herb Robert, the wood sorrel, the rose-bay willow herb, the enchanter’s nightshade, dog’s mercy, primrose, yellow pimpernel, fox-glove, ground ivy, wood sage, the bluebell, and numerous varieties of hay and rushes. Less common plants which grew in the woodland or near it were: the upright vetch, the wood horse-tail, the ivy-leaved bellflower, the mountain pansy, the sawwort, purging flax, woodruff, and the burnet saxifrage. Over a large area of Allt yr Hwch ground there was common cow-wheat, the bilberry and heather, sure indicators of the acidity of the soil in these places. Among the ordinary trees you would expect to find in these parts there were more unusual examples in this wood, such as the aspen, with its leaves quivering in the slightest breeze, so that the name of ‘Tafod Merched’ (Ladies Tongue) has also been ascribed to the tree. In addition, there was the small leaved lime, two of which were felled along with oaks and birches, ash and rowan-tree the broad-leaved elm, the alder and willow, beech and holly, the hawthorn and blackthorn and hazel. They were all felled within the Llyn Brianne basin up to a height of 915 feet before drowning the valley.

The Birds

The oak trees provided a home for many common resident birds such as the buzzard, the woodcock, the cuckoo, tawny owl, green woodpecker and great spotted woodpecker, the crow, jackdaw, jay, the great tit, the blue tit, the coal tit, marsh tit and long tailed tit, the nuthatch, treecreeper, wren, pied wagtail and thrush, the blackbird, robin, hedge-sparrow, starling, chaffinch and wood-pigeon. They had found shelter and nesting places in the trees. Spring saw the arrival of the migratory birds, such as the pied flycatcher, redstart, garden warbler, blackcap, chiff-chaff and wood warbler. Around the rivers and streams could be found the dipper, the common sandpiper and the wagtail. Peter Hope Jones noted the crossbill, greenfinch and black grouse in the Allt yr Hwch reserve while undertaking research into the latter bird.

The oak woods of the reserve and Coed-cae-gwartheg formed a nesting-place for the kite from time to time since the beginning of the century, when its numbers had decreased disastrously to about half a dozen pairs. When the guns of the keepers and the landowners’ poison had completely swept this magnificent bird of prey from the skies above England and Scotland, it found a sanctuary from its persecutors here in the upper reaches of the Tywi Valley; ‘it was here and here only that were seen the pitiful remnants of this bird which had been a common scavenger on the streets of London in the time of Shakespeare and of Samuel Pepys’. Here the first steps were taken to try to safeguard the bird, measures which proved successful despite the slow growth in the kite population and disappointments in some years. Thanks to the watchfulness of the farmers and the perseverance of the conservationists over a long period of time, the red kite (or Boda’r Wennol as it is called locally) as preserved only just in time and its future assured. The dozen or so birds at the turn of the century grew to the present population. (375 in August 1992). In an age which suffered so many losses in both animals and plant life and their environments, it is pleasing to be able to note success in this particular case.

The Gorges

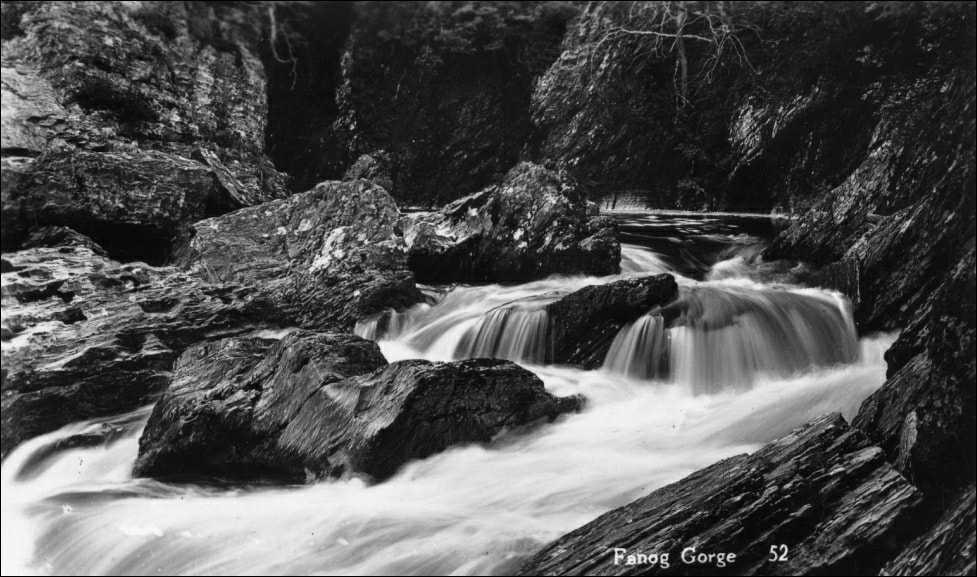

Another important environment threatened by the Llyn Brianne Order was the gorges. The gorges of the heads of the Tywi valley were fashioned by the water of the rivers and streams flowing rapidly from the mid-Wales plateau (Cambrian Mountains) and falling into the valleys as waterfalls, cataracts and springs. This process erodes the loose shale of the Silurian rock and forms deep ravines or gorges in the courses of the rivers and streams. In these gorges the light is poor and the air is damp. Water washes over the moveable soil of these gorges and these conditions create an ideal environment for certain plants, especially mosses, liverwort and ferns. The best examples from the gorges of the Upper Tywi valley vanished under the waters of Llyn Brianne, notably the gorge on the river Camddwr between Soar-y-Mynydd Chapel and its confluence with the Tywi and the very narrow gorge on the Tywi near the Fanog Farm. On both sides of the Allt yr Hwch there were gorges. Among the flowering plants of the nature reserve’s gorges which disappeared were the water avens and the globe flower. With the drowning of the river Camddwr we also lost the only colony known in the Upper Tywi Valley of the Welsh poppy.

In order to catalogue the mosses and liverworts which would disappear from the gorges of the reserve when the valley was submerged, Dr Derek Ratcliffe came here on March 33, 1967 as the leader of a group of three research students from the Botany School at Cambridge, namely Hilary Birks, John Birks and John Dransfield. On that date they noted 88 types of mosses and 34 liverworts.

The members of the Defence Committee tried to be constructive in their opposition to the Llyn Brianne water scheme. There was agreement that West Glamorgan needed a water supply and desalination of the sea water was suggested as an alternative to drowning a valley which had special natural features. The Water Board was asked to consider other sites for its reservoir; one which attracted special attention was the Upper Tywi. This site, about five miles up river from the site of the Llyn Brianne dam, had numerous advantages over the Brianne:

1. It was less damaging to the ecology of the area and to the natural beauty of the upper reaches of the Tywi Valley, and consequently it was not expected to draw much opposition from organisations concerned with nature preservation and with the beauty of Wales. The gorges would be safe-guarded and the oak woods of Allt yr Hwch and Coed-cae-Gwartheg preserved.

2. Less agricultural land would be drowned (almost all the land in this scheme was the property of the Forestry Commission) and there would, be less opposition by the farmers of the neighbourhood.

3. The Forestry Commission would lose many fewer roads and bridges, plantations and oak forests.

4. The dam would be higher up the river than the furthest point reached by migratory fish in the Tywi (the high waterfall near the Fanog prevented fish such as salmon and sewin from going further) and the damage to fisheries would be much less. There would be no need for a fish-ladder nor a dubious scheme to trap fish and convey them by lorry as was adopted for Llyn Brianne. Nor would it be necessary (as in the Llyn Brianne scheme) to release fish in a part of the river which they had never previously seen.

(Eventually this proved to be a total disaster and the fish traps were decommissioned).

5. Messrs. Binnie, Deacon and Gowley, consultant engineers to the Swansea County Borough Council (as the Swansea City Council) was then called reported as follows to The Council on the Upper Tywi scheme in July 1960: ‘The Towy (Upper) Scheme offers the greatest advantage to River Towy users as a whole by maintaining a higher dry weather flow over most of the non-tidal stretch. The reservoir would cause no serious inconvenience and the scheme is an example of the ideal type of river regulation.’ So the Upper Tywi Scheme which we had placed before the Water Board at the Inquiry was approved by Swansea’s own consulting engineers.

The Upper Tywi reservoir would provide a supply of 56 million gallons a day, but it was rejected because the supply was not sufficient to meet the Water Board’s requirements; in this context we should remember the particular effort made and bitter feelings aroused by the threat to take the Llangyndeyrn opponents to prison in order to achieve a reservoir supplying 25 million gallons a day. (Reservoir project – eventually abandoned in the face of understandably fierce local opposition before setting sights on the upper Tywi valley). When they came to the Tywi Valley immediately after the Llangyndeyrn confrontation, they became more greedy; a reservoir providing more than double the supply of Llangyndeyrn was not enough. Did the officers and councillors of Swansea, intend at the time on promoting the status of the town to that of a city, entertain ambitions to lay claim to having a reservoir with the highest dam in Britain? A childish and unworthy claim you might say? Possibly, but to those who were in the throes of the struggle, it is not without a grain of truth in it. It is doubtful whether they need all this water – 86 million gallons a day – when we consider what happened to industry in South Wales. It has contracted, many coal mines have closed, iron and steel production has been restricted and unemployment has increased.

The Inquiry closed on February 9, 1967. The Inspector, representatives of the West Glamorgan Water Board, the farmers and representatives of the organisations which had fought against the scheme, visited the proposed works and also the Upper Tywi site on February 13 and 14 1967. All that remained was to await the Inspector’s Report and the decision of the Secretary of State in the light of the Report.

By June 19, 1967 the Inspector had completed his Report and he submitted it to Cledwyn Hughes, the Secretary of State for Wales at the time. This was not known to the opponents of the scheme at that time, nor to anyone else, so far as I knew. Indeed, we had to wait until December 1967 to receive a copy of the Report from the Welsh Office and Mr Cledwyn Hughes’ decision: the verdict was to grant permission for the Llyn Brianne Water Scheme to go ahead. The battle was over and we had lost – but the dust had not yet settled.

Soon after the completion of the Report on June 19, 1967 (the date of the Report signed by Mr. A S R Mutch, the Inspector), a farmer who stood to lose land under the scheme brought some astounding news. While shepherding he had come across a Land Rover vehicle on his land. On the seat was a document with the following title page:

Another important environment threatened by the Llyn Brianne Order was the gorges. The gorges of the heads of the Tywi valley were fashioned by the water of the rivers and streams flowing rapidly from the mid-Wales plateau (Cambrian Mountains) and falling into the valleys as waterfalls, cataracts and springs. This process erodes the loose shale of the Silurian rock and forms deep ravines or gorges in the courses of the rivers and streams. In these gorges the light is poor and the air is damp. Water washes over the moveable soil of these gorges and these conditions create an ideal environment for certain plants, especially mosses, liverwort and ferns. The best examples from the gorges of the Upper Tywi valley vanished under the waters of Llyn Brianne, notably the gorge on the river Camddwr between Soar-y-Mynydd Chapel and its confluence with the Tywi and the very narrow gorge on the Tywi near the Fanog Farm. On both sides of the Allt yr Hwch there were gorges. Among the flowering plants of the nature reserve’s gorges which disappeared were the water avens and the globe flower. With the drowning of the river Camddwr we also lost the only colony known in the Upper Tywi Valley of the Welsh poppy.

In order to catalogue the mosses and liverworts which would disappear from the gorges of the reserve when the valley was submerged, Dr Derek Ratcliffe came here on March 33, 1967 as the leader of a group of three research students from the Botany School at Cambridge, namely Hilary Birks, John Birks and John Dransfield. On that date they noted 88 types of mosses and 34 liverworts.

The members of the Defence Committee tried to be constructive in their opposition to the Llyn Brianne water scheme. There was agreement that West Glamorgan needed a water supply and desalination of the sea water was suggested as an alternative to drowning a valley which had special natural features. The Water Board was asked to consider other sites for its reservoir; one which attracted special attention was the Upper Tywi. This site, about five miles up river from the site of the Llyn Brianne dam, had numerous advantages over the Brianne:

1. It was less damaging to the ecology of the area and to the natural beauty of the upper reaches of the Tywi Valley, and consequently it was not expected to draw much opposition from organisations concerned with nature preservation and with the beauty of Wales. The gorges would be safe-guarded and the oak woods of Allt yr Hwch and Coed-cae-Gwartheg preserved.

2. Less agricultural land would be drowned (almost all the land in this scheme was the property of the Forestry Commission) and there would, be less opposition by the farmers of the neighbourhood.

3. The Forestry Commission would lose many fewer roads and bridges, plantations and oak forests.

4. The dam would be higher up the river than the furthest point reached by migratory fish in the Tywi (the high waterfall near the Fanog prevented fish such as salmon and sewin from going further) and the damage to fisheries would be much less. There would be no need for a fish-ladder nor a dubious scheme to trap fish and convey them by lorry as was adopted for Llyn Brianne. Nor would it be necessary (as in the Llyn Brianne scheme) to release fish in a part of the river which they had never previously seen.

(Eventually this proved to be a total disaster and the fish traps were decommissioned).

5. Messrs. Binnie, Deacon and Gowley, consultant engineers to the Swansea County Borough Council (as the Swansea City Council) was then called reported as follows to The Council on the Upper Tywi scheme in July 1960: ‘The Towy (Upper) Scheme offers the greatest advantage to River Towy users as a whole by maintaining a higher dry weather flow over most of the non-tidal stretch. The reservoir would cause no serious inconvenience and the scheme is an example of the ideal type of river regulation.’ So the Upper Tywi Scheme which we had placed before the Water Board at the Inquiry was approved by Swansea’s own consulting engineers.

The Upper Tywi reservoir would provide a supply of 56 million gallons a day, but it was rejected because the supply was not sufficient to meet the Water Board’s requirements; in this context we should remember the particular effort made and bitter feelings aroused by the threat to take the Llangyndeyrn opponents to prison in order to achieve a reservoir supplying 25 million gallons a day. (Reservoir project – eventually abandoned in the face of understandably fierce local opposition before setting sights on the upper Tywi valley). When they came to the Tywi Valley immediately after the Llangyndeyrn confrontation, they became more greedy; a reservoir providing more than double the supply of Llangyndeyrn was not enough. Did the officers and councillors of Swansea, intend at the time on promoting the status of the town to that of a city, entertain ambitions to lay claim to having a reservoir with the highest dam in Britain? A childish and unworthy claim you might say? Possibly, but to those who were in the throes of the struggle, it is not without a grain of truth in it. It is doubtful whether they need all this water – 86 million gallons a day – when we consider what happened to industry in South Wales. It has contracted, many coal mines have closed, iron and steel production has been restricted and unemployment has increased.

The Inquiry closed on February 9, 1967. The Inspector, representatives of the West Glamorgan Water Board, the farmers and representatives of the organisations which had fought against the scheme, visited the proposed works and also the Upper Tywi site on February 13 and 14 1967. All that remained was to await the Inspector’s Report and the decision of the Secretary of State in the light of the Report.

By June 19, 1967 the Inspector had completed his Report and he submitted it to Cledwyn Hughes, the Secretary of State for Wales at the time. This was not known to the opponents of the scheme at that time, nor to anyone else, so far as I knew. Indeed, we had to wait until December 1967 to receive a copy of the Report from the Welsh Office and Mr Cledwyn Hughes’ decision: the verdict was to grant permission for the Llyn Brianne Water Scheme to go ahead. The battle was over and we had lost – but the dust had not yet settled.

Soon after the completion of the Report on June 19, 1967 (the date of the Report signed by Mr. A S R Mutch, the Inspector), a farmer who stood to lose land under the scheme brought some astounding news. While shepherding he had come across a Land Rover vehicle on his land. On the seat was a document with the following title page:

WEST GLAMORGAN WATER BOARD

RIVER TOWY SCHEME

Contract No. 3

ROAD DIVERSION AND IMPROVEMENT WORKS

Instruction for Tenders

Conditions of Contract

Specifications

Bills of Quantities

Tender

1967

RIVER TOWY SCHEME

Contract No. 3

ROAD DIVERSION AND IMPROVEMENT WORKS

Instruction for Tenders

Conditions of Contract

Specifications

Bills of Quantities

Tender

1967

Iorwerth J. Watkins, Esq. Binnie & Partners

Acting Clerk Chartered Civil Engineers,

The West Glamorgan Water Board Artillery House,

Swansea, Artillery Row,

Glamorgan, London, S. W. 1.

Acting Clerk Chartered Civil Engineers,

The West Glamorgan Water Board Artillery House,

Swansea, Artillery Row,

Glamorgan, London, S. W. 1.

It is instructive to quote to quote one of the ‘Instructions to Tenders’: ‘IT.4 One completed copy of the bound document shall be addressed in a plain cover, marked ‘Tender for River Towy Scheme, Contract No. 3’ but bearing no mark by which the identity of the Tender might be ascertained, and shall be delivered to the Acting Clerk, The West Glamorgan Water Board, The Guildhall, Swansea, Glamorgan, not later than August 11, 1967.’

As can be seen, the date by when the tender was to be in the hands of the clerk to the Water Board was four months earlier than the Secretary of State’s decision that the scheme was to go ahead !

At the request of the Defence Committee, the matter was raised in Parliament by Alderman Tudor Watkins, Member of Parliament for Brecon and Radnor. When the Water Board was accused of going ahead before the Secretary of State had come to a decision, the reply was that the Board was trying to save time. If so why did not the Board not announce its intention to seek permission from the farmers and tenants to go on their land? Moreover, there was no mention in Contract No. 3 (a document of 58 pages) that it depended upon a favourable decision by the Secretary of State, nor was there any reference to compensation for the tenders if the contract failed to develop. Distributed at the same time as Contract No. 3 was Contract No. 4 relating to the pipe (under dam wall), and Contract No. 5 which referred to the tunnel at Tumble (transferring water from the river to a storage installation).

Following Tudor Watkins’ Parliamentary question, a report appeared in the ‘Western Mail’ on July 13, 1967 entitled: ‘Welsh Office raps reservoir moves’. The Welsh Office’s meek response was the mild rebuke ‘We are aware that this is going on and we have reminded the West Glamorgan Water Board that the Secretary of State has not yet announced his decision’. The Water Board’s action in inviting tenders six months before Cledwyn Hughes came to a decision on the scheme left a bitter taste behind it and cynicism towards the ‘democratic’ process of a Public Inquiry. The impression gained by the opponents of the scheme was that the members of the Water Board knew beforehand what the Secretary of State’s decision would be!

As a footnote to the Llyn Brianne campaign, it is worth noting that a similar case was proceeding at the same time in Upper Teesdale in Durham. In that instance the Cleveland and Tees Valley Water Board wished to build a reservoir in the Cow Green area above Caldron Snout in Upper Teesdale to meet the needs of ICI (Imperial Chemical Industries) on Teeside. Attempts were made at a national and international level to save the area from being drowned. In the vanguard was the Botanical Society of the British Isles, because the site was unique in the botanical sense. At risk were rare floral specimens. The presence of a large number of Arctic/Alpine plants so far from their usual habitats made this site of the greatest interest to botanists and the sum of £5000 was raised in order to fight the campaign. (considerable sum in the 1960’s). Botanists of the greatest standing gave testimony, but just as the opponents of the Llyn Brianne scheme, the Botanical Society was also defeated in Upper Teesdale. At the time of these campaigns, public awareness of the environment was much less than today, I wonder whether the results would be similar if the inquiries were to be conducted today ?

Dafydd Dafis.

Published 1993

NOTE.

For anyone who knows the Doethie valley, surely will agree that this is one of the most beautiful places in Wales. The fact that the defence committee thwarted the plan to build a main road through a part of this valley was in my view a victory in itself. As you will see from the preceding account from Dafydd Dafis the building of this reservoir was more or less a foregone conclusion from the start and the public enquiry was merely a formality.

I will leave the last words to the writer Jim Perrin…….

……‘There are many places in Wales of which I am fond, all of them entrancing in their different ways and at their proper seasons. But if I were asked by a stranger to this loveliest of all countries which place is the most beautiful, then I would tell of the pleasure in walking up the Afon Doethie on a fine day in the high spring of May or June when hawthorn blossom beacons the hillsides and bluebells shimmer like a low flame amongst the woods.’

…..’It’s reached from Rhandirmwyn by walking up towards the new reservoir of Llyn Brianne, the disfigured hand-shape of which grasped too much of Wales’ beauty when it drowned the infant streams of Camddwr and Craflwyn, Tywi and Nant Gwrach. Those culpable surveyors looked, no doubt, at the adjacent valleys of the Doethie and the Pysgotwr, and I don’t for a moment disbelieve that they are capable of looking there again (at Blaen Doethie currently there are plans to install a huge wind-farm development, which would be desecration here)’.

Jim Perrin has long been recognised as the finest of British mountaineering and outdoor writers, with regular, outstanding features in the Daily Telegraph, Climber and The Great Outdoor.

He gets his joy and expresses it like a poet, from solitude and nature.’ - The Observer

The wind-farm is still only a proposal. Lets hope it stays that way. That really would be the final nail in the coffin of this the most beautiful, picturesque part of Wales you can imagine.