Bywyd Gwledig

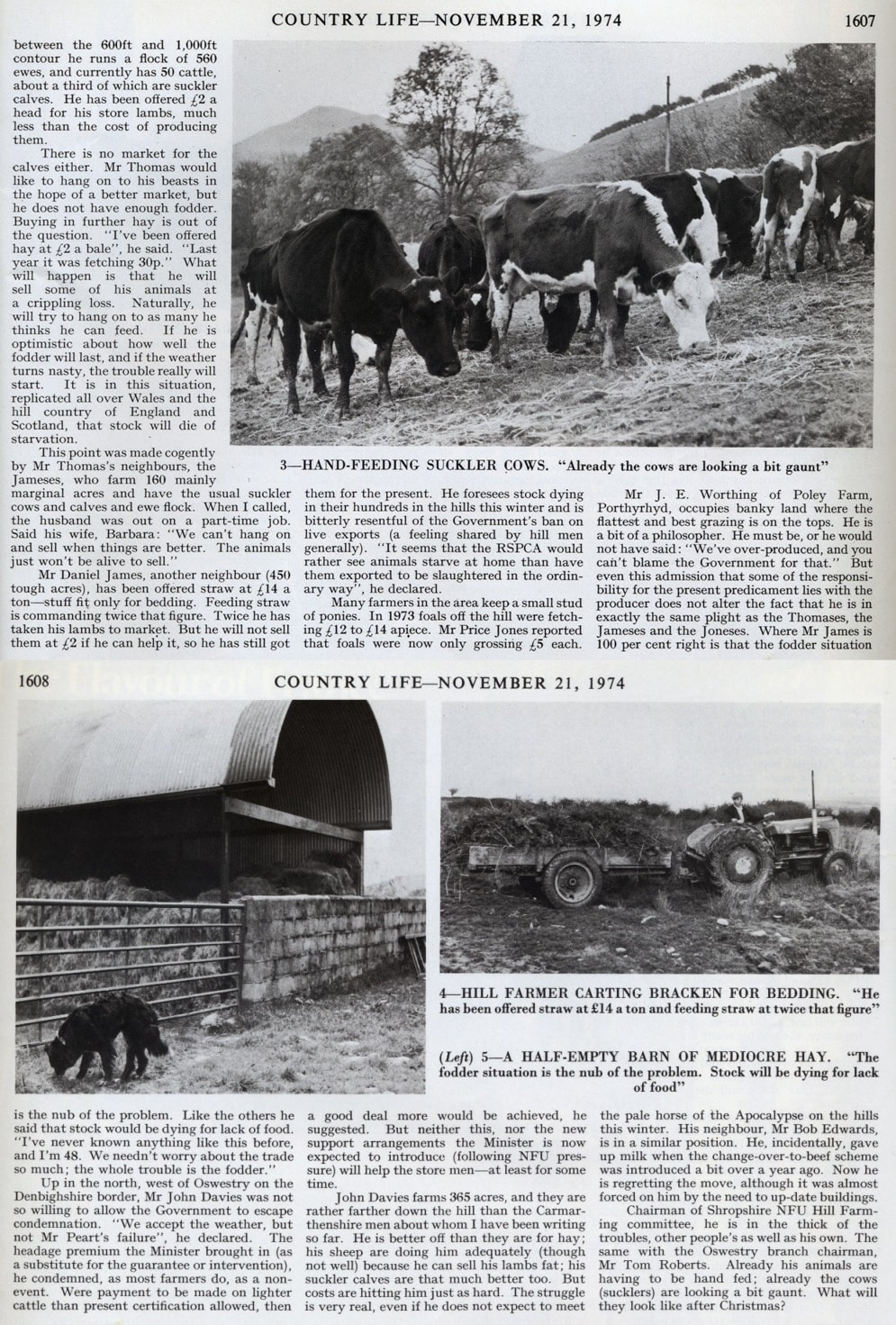

Mae’r dudalen hon yn ymwneud â materion cefn gwlad sy’n rhan o fywyd Rhandir-mwyn ers blynyddoedd lawer - am ganrifoedd yn aml. Cafodd y rhain eu dosbarthu yn ôl y penawdau a ganlyn:

Ffermio – dyma un o brif ddiwydiannau Rhandir-mwyn ers canrifoedd. Roedd gan Fynaich Gwynion Ystrad Fflur faenor, tir amaethyddol a melin flawd yn Nant-y-bai yn y 12fed ganrif.

Coedwigaeth – daeth y diwydiant hwn i Randir-mwyn a Blaenau Tywi yn y 1950au. Y bwriad gwreiddiol oedd prynu’r holl ddyffryn drwy orfodaeth a’i orchuddio’n gyfan gwbl â chonwydd. Bu gwrthwynebiad cryf gan ffermwyr a thrigolion lleol a chynhaliwyd ymchwiliad cyhoeddus. Diolch i’r drefn, bu newid Llywodraeth a chafodd y cynllun ei roi o’r neilltu. Ymhen rhai blynyddoedd, fodd bynnag, gwerthodd rhai ffermwyr eu tir i’r Comisiwn Coedwigaeth a daeth Coedwig Tywi i fodolaeth. Roedd hyn yn fendith mewn sawl ffordd oherwydd bu coedwigaeth, am nifer o flynyddoedd, yn brif gyflogwr y dyffryn. Y dyddiau hyn (2011) mae llawer o’r coed a blannwyd yn y 1950au a’r 1960au yn cael eu cwympo ac mae’r pren yn cael ei ddefnyddio i gynhyrchu papur, dodrefn gardd a thanwydd i orsafoedd pŵer .

Ffermio – dyma un o brif ddiwydiannau Rhandir-mwyn ers canrifoedd. Roedd gan Fynaich Gwynion Ystrad Fflur faenor, tir amaethyddol a melin flawd yn Nant-y-bai yn y 12fed ganrif.

Coedwigaeth – daeth y diwydiant hwn i Randir-mwyn a Blaenau Tywi yn y 1950au. Y bwriad gwreiddiol oedd prynu’r holl ddyffryn drwy orfodaeth a’i orchuddio’n gyfan gwbl â chonwydd. Bu gwrthwynebiad cryf gan ffermwyr a thrigolion lleol a chynhaliwyd ymchwiliad cyhoeddus. Diolch i’r drefn, bu newid Llywodraeth a chafodd y cynllun ei roi o’r neilltu. Ymhen rhai blynyddoedd, fodd bynnag, gwerthodd rhai ffermwyr eu tir i’r Comisiwn Coedwigaeth a daeth Coedwig Tywi i fodolaeth. Roedd hyn yn fendith mewn sawl ffordd oherwydd bu coedwigaeth, am nifer o flynyddoedd, yn brif gyflogwr y dyffryn. Y dyddiau hyn (2011) mae llawer o’r coed a blannwyd yn y 1950au a’r 1960au yn cael eu cwympo ac mae’r pren yn cael ei ddefnyddio i gynhyrchu papur, dodrefn gardd a thanwydd i orsafoedd pŵer .

Helfa Tywi a Chothi – Bu hela’n draddodiad pwysig yn y dyffryn yn ystod y ganrif a aeth heibio. Yma, gallwch ddarllen hanes Helfa Rhandir-mwyn – a newidiodd ei enw yn ddiweddarach i Helfa Tywi a Chothi.

Sioe a Threialon Cŵn Defaid Rhandir-mwyn – cynhelir y sioe a threialon cŵn defaid o hyd ddydd Sadwrn Gŵyl Banc mis Awst. Yma, rhown hanes y sioe o’i dyddiau cynnar ar fferm Bron-cwrt hyd nes iddi symud i'w safle presennol ar fferm Pwllpriddog.

Diddordebau a Thraddodiadau Cefn Gwlad – y traddodiadau hynny a oedd ambell waith yn unigryw i’r ardal.

Sioe a Threialon Cŵn Defaid Rhandir-mwyn – cynhelir y sioe a threialon cŵn defaid o hyd ddydd Sadwrn Gŵyl Banc mis Awst. Yma, rhown hanes y sioe o’i dyddiau cynnar ar fferm Bron-cwrt hyd nes iddi symud i'w safle presennol ar fferm Pwllpriddog.

Diddordebau a Thraddodiadau Cefn Gwlad – y traddodiadau hynny a oedd ambell waith yn unigryw i’r ardal.

Ffermio

Arferai Rhandir-mwyn fod yn bentref diwydiannol, ond os ydych chi’n ymchwilio i hanes lleol fe welwch fod amaethyddiaeth yn bwysig dros ben. Dros y canrifoedd mae llawer o drigolion yr ardal wedi byw ar ffermydd helaeth neu ar dyddynnod ag ychydig erwau o dir. Byddai llawer o’r tyddynwyr yn cael bywoliaeth yn y gweithfeydd plwm. Mae hen gofnodion yn dangos fod ffermwyr yn defnyddio ceffyl a chert i gludo’r plwm o waith plwm Nant-y-mwyn i Lanymddyfri. Mae’n rhaid bod yr incwm yn dderbyniol iawn oherwydd mae ffermio wastad wedi bod yn anodd.

Y dyddiau hyn fe welwch taw dim ond ychydig o ffermydd teuluol sydd ar ôl ym Mlaenau Tywi. Gwerthwyd llawer a chafodd y tai maes eu troi’n anheddau. Gwerthwyd y tir i ffermwyr eraill, ac mae’r tir hwnnw yn ei dro wedi dod yn rhan o ddaliadau mwy byth o faint.

Mae hanes ffermio yn ddiddorol a gobeithiwn roi ychydig o flas y dyddiau a fu i chi.

Mae llawer o’r ffermydd yn bwysig yn hanesyddol.

Cymerwch Fferm Dugoedydd, er enghraifft. Yn y ffermdy hwn, rhwng Rhandir-mwyn a Chil-y-cwm, y cynhaliwyd Sasiwn gyntaf y Methodistiaid Calfinaidd ar 7 Ionawr 1742.

Mae Fferm Ystrad-ffin yn dyddio’n ôl i'r bymthegfed ganrif ac yn gynharach yn fwy na thebyg. Mae ganddi gysylltiad agos â Thomas Jones (Twm Siôn Cati) a arferai guddio mewn ogof ar dir a oedd bryd hynny yn rhan o’r fferm. Tua 1607, priododd weddw o’r enw Joan a oedd yn byw ar fferm Ystrad-ffin. Heddiw, mae’n dal i fod yn fferm deuluol. Bu’n eiddo i'r un teulu ers cenedlaethau a hir y parhaed felly.

Mae ffermydd Troedrhiwcymmer a Throedrhiwrhuddwen yng Nghwm Doethie. Hyd at y 1960au hwyr, y teulu Jones, sef teulu adnabyddus ac uchel ei barch, oedd yn ffermio’r ddwy. Roedd Jane a William Jones ar flaen y gad yn gwrthwynebu coedwigo a boddi tir i greu cronfa Llyn Brianne. Roedden nhw’n bobl nodedig. Caiff eu hanes ei gynnwys cyn bo hir.

Hefyd, byddwn yn cynnwys atgofion Tommy Williams a’r diweddar Olwen Price, ffermwyr a phobl Rhandir-mwyn o’r iawn ryw.

Mae llawer mwy ar y ffordd.

Os oes gennych unrhyw wybodaeth neu luniau, cofiwch gysylltu. [email protected]

Y dyddiau hyn fe welwch taw dim ond ychydig o ffermydd teuluol sydd ar ôl ym Mlaenau Tywi. Gwerthwyd llawer a chafodd y tai maes eu troi’n anheddau. Gwerthwyd y tir i ffermwyr eraill, ac mae’r tir hwnnw yn ei dro wedi dod yn rhan o ddaliadau mwy byth o faint.

Mae hanes ffermio yn ddiddorol a gobeithiwn roi ychydig o flas y dyddiau a fu i chi.

Mae llawer o’r ffermydd yn bwysig yn hanesyddol.

Cymerwch Fferm Dugoedydd, er enghraifft. Yn y ffermdy hwn, rhwng Rhandir-mwyn a Chil-y-cwm, y cynhaliwyd Sasiwn gyntaf y Methodistiaid Calfinaidd ar 7 Ionawr 1742.

Mae Fferm Ystrad-ffin yn dyddio’n ôl i'r bymthegfed ganrif ac yn gynharach yn fwy na thebyg. Mae ganddi gysylltiad agos â Thomas Jones (Twm Siôn Cati) a arferai guddio mewn ogof ar dir a oedd bryd hynny yn rhan o’r fferm. Tua 1607, priododd weddw o’r enw Joan a oedd yn byw ar fferm Ystrad-ffin. Heddiw, mae’n dal i fod yn fferm deuluol. Bu’n eiddo i'r un teulu ers cenedlaethau a hir y parhaed felly.

Mae ffermydd Troedrhiwcymmer a Throedrhiwrhuddwen yng Nghwm Doethie. Hyd at y 1960au hwyr, y teulu Jones, sef teulu adnabyddus ac uchel ei barch, oedd yn ffermio’r ddwy. Roedd Jane a William Jones ar flaen y gad yn gwrthwynebu coedwigo a boddi tir i greu cronfa Llyn Brianne. Roedden nhw’n bobl nodedig. Caiff eu hanes ei gynnwys cyn bo hir.

Hefyd, byddwn yn cynnwys atgofion Tommy Williams a’r diweddar Olwen Price, ffermwyr a phobl Rhandir-mwyn o’r iawn ryw.

Mae llawer mwy ar y ffordd.

Os oes gennych unrhyw wybodaeth neu luniau, cofiwch gysylltu. [email protected]

Faming on Erwrhwch

(Recollections of Miss Alice Harries, Erwrhwch)

When Miss Alice Harries was a young girl on Erwrhwch Farm it was usual for them to grow crops of wheat, oats and barley.

The sheaves were left on the fields to dry. Should rain threaten, then the sheaves were stacked in a cone –shaped structure called ‘cogwrn’. There was quite an art to their construction and the grain had to be directed inwards to the centre of the stack to protect it from the rain. The sheaves were stored in the granary but in good years when the barns were full stacks called, ‘helmau’ were built; these were roofed with rushes obtained from wet, boggy places.

When Miss Alice Harries was a young girl on Erwrhwch Farm it was usual for them to grow crops of wheat, oats and barley.

The sheaves were left on the fields to dry. Should rain threaten, then the sheaves were stacked in a cone –shaped structure called ‘cogwrn’. There was quite an art to their construction and the grain had to be directed inwards to the centre of the stack to protect it from the rain. The sheaves were stored in the granary but in good years when the barns were full stacks called, ‘helmau’ were built; these were roofed with rushes obtained from wet, boggy places.

The machine seen in the picture was used to thresh the corn and to chaff the straw which was fed to the animals. Two horses were used for chaffing but three were necessary for threshing. The pigs were fed on barley and the horses on oats.

The Shearing Day

MEMORIES OF NANSI JONES, DALAR FARM, UPPER TYWI VALLEY

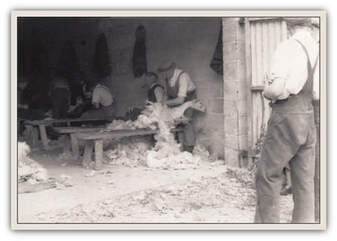

How vivid are my childhood memories of the shearing which I would like to record, as it was then.

The shearing season lasted about a month. Each farm would have its own day in the calendar month, such as the last Thursday in June which brings back poignant memories for me. I always observe the weather on that particular day in June each year, having experienced rather wet shearing days, other years one would be blessed with a fine day. If one was unable to carry on with the shearing owing to the rain then that farm would have a second shearing day at the end of the season, such was the community spirit that prevailed as those present at the first shearing gave their services willingly.

It was the custom for hill farmers to assist one another, they would ride across the hill to the farm where the shearing was to be held. On arrival they were greeted and invited into the farm house for light refreshment and a cup of tea would be very welcome as many of the men would have to ride several miles that morning, their ponies would be kept in a paddock for the rest of the day where they would graze and rest until they were required to take their rider home at the end of the day.

I would love to gaze at so many Welsh Mountain ponies in the same paddock, a truly magnificent sight, I only wish that colour photography had been available at the time to have captured such wealth of colour. I well remember the Chestnuts and the Dapple Greys with the flaxen mane and tail, Black ponies with white socks, also White, Cream and Strawberry Roan ponies, their tails moving slowly with the gentle upland breeze.

The men would put on their overalls and take their place on the shearing bench in the barn then the serious business of the day would take place. The more experienced shearers clipped the lambs, and the young men who were on their first season took their place alongside the men that sheared the sheep. Although the shearers were the stars of the shearing, the operation would not have been possible without the support role of the others.

Vagrants would make their way onto the hills for the shearing season, much was expected of them, they rose to the challenge for they were truly stalwart, they slept rough in the farm buildings and with the break of dawn they would go on their way walking across the hills to the next farm where the shearing was to be held carrying their few personal possessions wrapped into a bundle. Their status could only be described as absolute poverty. Very little if anything was known of their background, it was as if they wished to draw a veil over their past; surely this was their prerogative, they had no other privileges that I could think of.

They were the catchers and carriers. The catcher would be in the pen with the unshorn sheep, adjacent to the barn and the catcher would have a sheep caught ready to hand over to the ‘up’ carrier who would take the sheep to the shearer waiting at the bench. He would call out ‘string’ and the person in charge would gather a piece of string in his hand and with a flick of the wrist thrust it towards the shearer who would quickly catch it, and then tie the sheep’s legs together.

Now this practice may seem cruel to the urban dweller, but it was done as a protection for the animal being shorn, should it give an unexpected jerk if the legs were not tied together the naked blade of the shears could penetrate the skin and cause a nasty gash. With the modern method of shearing with the power driven machine the legs are not tied together as the head of the machine is similar in principal to the barber head clippers and gives better protection.

When the sheep had been shorn the shearer would call out ‘down carrier’, then the down carrier would swiftly move towards the bench and place his left arm through the animals legs and he would cradle the sheep’s head in his right hand and carry it out of the barn, placing it down gently on a bed of rushes, meanwhile the ‘up carrier’ would fetch a sheep from the catcher and take it along to the shearer.

A bench was placed along the outside wall of the barn and facing the bed of rushes, this bench, was occupied by the men who had served their time on the shearing bench, but each one had a task to perform. I would think of them as the elder statesmen of the shearing. One man would pitch and was known as the pitcher, he would move along the shorn sheep, stamping the flock individual pitch on the sheep and it was with pride that I watched the letter ‘W’ for William a family name appear on the shorn sheep and I felt that I too belonged to the shearing day although too tender of age to be allocated any task.

The pitcher would cast his eye over the shorn sheep, if he spotted a small cut on any animal he would call out ‘doctor’, now that was not as alarming as it sounds as this was the person in charge of the tar. He would cover the cut with tar as a protection from flies until the skin healed.

The wool would be gathered in a large square of sacking, taken to the wool shed where the fleece was packed into a bundle that was secured by teasing the neck wool into a rope, which was then wrapped around the bundle. The lamb clippings were put into a separate sack.

How vivid are my childhood memories of the shearing which I would like to record, as it was then.

The shearing season lasted about a month. Each farm would have its own day in the calendar month, such as the last Thursday in June which brings back poignant memories for me. I always observe the weather on that particular day in June each year, having experienced rather wet shearing days, other years one would be blessed with a fine day. If one was unable to carry on with the shearing owing to the rain then that farm would have a second shearing day at the end of the season, such was the community spirit that prevailed as those present at the first shearing gave their services willingly.

It was the custom for hill farmers to assist one another, they would ride across the hill to the farm where the shearing was to be held. On arrival they were greeted and invited into the farm house for light refreshment and a cup of tea would be very welcome as many of the men would have to ride several miles that morning, their ponies would be kept in a paddock for the rest of the day where they would graze and rest until they were required to take their rider home at the end of the day.

I would love to gaze at so many Welsh Mountain ponies in the same paddock, a truly magnificent sight, I only wish that colour photography had been available at the time to have captured such wealth of colour. I well remember the Chestnuts and the Dapple Greys with the flaxen mane and tail, Black ponies with white socks, also White, Cream and Strawberry Roan ponies, their tails moving slowly with the gentle upland breeze.

The men would put on their overalls and take their place on the shearing bench in the barn then the serious business of the day would take place. The more experienced shearers clipped the lambs, and the young men who were on their first season took their place alongside the men that sheared the sheep. Although the shearers were the stars of the shearing, the operation would not have been possible without the support role of the others.

Vagrants would make their way onto the hills for the shearing season, much was expected of them, they rose to the challenge for they were truly stalwart, they slept rough in the farm buildings and with the break of dawn they would go on their way walking across the hills to the next farm where the shearing was to be held carrying their few personal possessions wrapped into a bundle. Their status could only be described as absolute poverty. Very little if anything was known of their background, it was as if they wished to draw a veil over their past; surely this was their prerogative, they had no other privileges that I could think of.

They were the catchers and carriers. The catcher would be in the pen with the unshorn sheep, adjacent to the barn and the catcher would have a sheep caught ready to hand over to the ‘up’ carrier who would take the sheep to the shearer waiting at the bench. He would call out ‘string’ and the person in charge would gather a piece of string in his hand and with a flick of the wrist thrust it towards the shearer who would quickly catch it, and then tie the sheep’s legs together.

Now this practice may seem cruel to the urban dweller, but it was done as a protection for the animal being shorn, should it give an unexpected jerk if the legs were not tied together the naked blade of the shears could penetrate the skin and cause a nasty gash. With the modern method of shearing with the power driven machine the legs are not tied together as the head of the machine is similar in principal to the barber head clippers and gives better protection.

When the sheep had been shorn the shearer would call out ‘down carrier’, then the down carrier would swiftly move towards the bench and place his left arm through the animals legs and he would cradle the sheep’s head in his right hand and carry it out of the barn, placing it down gently on a bed of rushes, meanwhile the ‘up carrier’ would fetch a sheep from the catcher and take it along to the shearer.

A bench was placed along the outside wall of the barn and facing the bed of rushes, this bench, was occupied by the men who had served their time on the shearing bench, but each one had a task to perform. I would think of them as the elder statesmen of the shearing. One man would pitch and was known as the pitcher, he would move along the shorn sheep, stamping the flock individual pitch on the sheep and it was with pride that I watched the letter ‘W’ for William a family name appear on the shorn sheep and I felt that I too belonged to the shearing day although too tender of age to be allocated any task.

The pitcher would cast his eye over the shorn sheep, if he spotted a small cut on any animal he would call out ‘doctor’, now that was not as alarming as it sounds as this was the person in charge of the tar. He would cover the cut with tar as a protection from flies until the skin healed.

The wool would be gathered in a large square of sacking, taken to the wool shed where the fleece was packed into a bundle that was secured by teasing the neck wool into a rope, which was then wrapped around the bundle. The lamb clippings were put into a separate sack.

The man in charge of the count would have a notebook marked into columns with the following headings. Rams, Ram lambs, Ewes, Ewe lambs, Weathers, he would count in tens, which meant that each stroke in the book would equal ten in number. Having been counted their legs would be untied and they would stand up, shake themselves and leap into the air and they were away back to the mountains. The men worked hard and the hours were long, but it was a happy time, they were merry men joking and teasing one another, good naturedly, and the sound of their laughter echoed through the old stone barn.

The flock of sheep had to be brought down from the mountains, this was known as gathering, and required both skill and patience and was usually done on the previous evening. The neighbouring farmers would at the appointed time turn the sheep that would be nearest their particular boundary towards the centre of the mountains, then they would all meet up and then turn the flock into a paddock near the farm buildings.

One could not forget the shepherd’s best friend his beloved sheep dog, it could be seen at its best as it ran out onto the open hill, turning the sheep towards home and understanding each command from its master either by voice or whistle. This exercise was probably the origin of the sport known as sheepdog trials.

The ladies also contributed to the shearing, they were responsible for the catering, bread and fruitcake would have been baked in large ovens in the farmhouse kitchen. A hot meal was provided at mid-day and the usual afternoon tea and another snack before they saddled their ponies for the homeward journey. As I surveyed the scene years later I couldn’t see anything had changed and it seemed that it would always remain that way. We live in an ever changing world, the hills became too sparsely populated with many of the younger generation leaving the hills to seek pastures new so different methods had to be found and the shearing has been taken over by contractors. The lone shearer riding his sure footed little stead over the mountain paths that he knew so well carrying his hand shears in a leather sheath has passed into history.

A familiar sight during the shearing season is a four wheel drive vehicle making its way along the mountain track conveying the contractor and his shears bringing their power driven machines with them, their destination being the farm where the gathering has been done in readiness for their arrival to honour the agreement to shear the flock of sheep.

May I wish them well.

NANSI JONES

The late Nansi Jones, known to all locals as ‘Nansi Dalar’ was born in Dalar Wen Farm located in the upper Tywi valley above Rhandirmwyn. The farmhouse still exists and is located at the side of Llyn Brianne reservoir. It is now a holiday home. Many of Nansi’s relatives lived and farmed in these hills as some still do today.

The flock of sheep had to be brought down from the mountains, this was known as gathering, and required both skill and patience and was usually done on the previous evening. The neighbouring farmers would at the appointed time turn the sheep that would be nearest their particular boundary towards the centre of the mountains, then they would all meet up and then turn the flock into a paddock near the farm buildings.

One could not forget the shepherd’s best friend his beloved sheep dog, it could be seen at its best as it ran out onto the open hill, turning the sheep towards home and understanding each command from its master either by voice or whistle. This exercise was probably the origin of the sport known as sheepdog trials.

The ladies also contributed to the shearing, they were responsible for the catering, bread and fruitcake would have been baked in large ovens in the farmhouse kitchen. A hot meal was provided at mid-day and the usual afternoon tea and another snack before they saddled their ponies for the homeward journey. As I surveyed the scene years later I couldn’t see anything had changed and it seemed that it would always remain that way. We live in an ever changing world, the hills became too sparsely populated with many of the younger generation leaving the hills to seek pastures new so different methods had to be found and the shearing has been taken over by contractors. The lone shearer riding his sure footed little stead over the mountain paths that he knew so well carrying his hand shears in a leather sheath has passed into history.

A familiar sight during the shearing season is a four wheel drive vehicle making its way along the mountain track conveying the contractor and his shears bringing their power driven machines with them, their destination being the farm where the gathering has been done in readiness for their arrival to honour the agreement to shear the flock of sheep.

May I wish them well.

NANSI JONES

The late Nansi Jones, known to all locals as ‘Nansi Dalar’ was born in Dalar Wen Farm located in the upper Tywi valley above Rhandirmwyn. The farmhouse still exists and is located at the side of Llyn Brianne reservoir. It is now a holiday home. Many of Nansi’s relatives lived and farmed in these hills as some still do today.