The Old School

As you will see education was very important in this little corner of Wales and it was a very sad day when the school finally closed in December 1969. We include an account of the history of Rhandirmwyn school as told ably by the last headmaster Mr Dafydd Dafis.

Rhandirmwyn school was not just a school it was also an integral part of community life. It was often transformed into a concert hall. During the war, ‘welcome home’, concerts would be arranged for the local soldiers who came home on leave. The compere was the very able Mr David Thomas, Nantgwyn Farm who kept the audience enthralled with his humour and wonderful tales. An array of local talent would get up onto the stage and sing, read poetry and pay tribute to the young man or men who soon after would have to return to war.

The school was also a centre where the community would meet when there was a crisis, such as the proposed Llyn Brianne scheme or anything else which involved a gathering of the local people.

I recollect as a child many wonderful concerts and occasional dramas held on the improvised stage.

As well as the account about its history you will also find photographs of the school throughout the years, extracts from the school log and a section about the wartime evacuated Woodmansterne Road School, Streatham, London.

We are very much indebted to Mr Dafydd Dafis, Christine Lane and many former pupils of Rhandirmwyn school for their contributions.

If you have any old photographs or information about the school, please contact us [email protected] . If you want to contact old friends please leave a message on the message page and contact can be made via the website.

Alun Jones

Rhandirmwyn school was not just a school it was also an integral part of community life. It was often transformed into a concert hall. During the war, ‘welcome home’, concerts would be arranged for the local soldiers who came home on leave. The compere was the very able Mr David Thomas, Nantgwyn Farm who kept the audience enthralled with his humour and wonderful tales. An array of local talent would get up onto the stage and sing, read poetry and pay tribute to the young man or men who soon after would have to return to war.

The school was also a centre where the community would meet when there was a crisis, such as the proposed Llyn Brianne scheme or anything else which involved a gathering of the local people.

I recollect as a child many wonderful concerts and occasional dramas held on the improvised stage.

As well as the account about its history you will also find photographs of the school throughout the years, extracts from the school log and a section about the wartime evacuated Woodmansterne Road School, Streatham, London.

We are very much indebted to Mr Dafydd Dafis, Christine Lane and many former pupils of Rhandirmwyn school for their contributions.

If you have any old photographs or information about the school, please contact us [email protected] . If you want to contact old friends please leave a message on the message page and contact can be made via the website.

Alun Jones

History

History of Education in Rhandirmwyn By Dafydd Dafis, Tŷ’r Ysgol, Rhandirmwyn

Early Education - The National School - The Curriculum - Attendance - Rhandirmwyn School Head teachers

Early Education

Rhandirmwyn’s first school was held at Capel Peulin (St Paulinus’ Chapel), Ystradffin, owned in the Middle Ages by the Cistercians of Ystrad Fflur. The area was of special interest to the Cistercians because they owned the large Nant-y-Bai Farm (or ‘Nant Bey’ as was shown on the early maps of the Abbey Granges); this is also the location of Capel Peulin. Here Griffith Jones established one of his schools in a small, remote chapel in the middle of an area of remarkable natural beauty.

Griffith Jones (1683 – 1761) was a native of Penboyr, Carmarthenshire. He received his early education at Carmarthen Grammar School and was ordained in 1708. While serving as a curate at Laugharne he became a teacher at the SPCK School (the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge) and there he felt the desire to establish Welsh Circulating Schools. He moved to Llanddowror as a rector in 1716, remaining there for 25 years and henceforth became known as ‘Griffith Jones Llanddowror’. He was granted the rectorship by his friend and patron, Sir John Phillips and their friendship was further cemented when he married Sir John’s sister, Margaret in 1720.

Griffith Jones founded his first school in 1731, in Llanddowror in his native county. He then decided to establish more schools in the surrounding area. Teachers would serve for up to three months at one school before moving on to the next. In this way a large number of schools were founded by using a relatively small number of teachers. Usually in the winter months, the school would be held when there were less duties to be performed on the farms. Children and adults were taught to read the Scriptures in their native tongue and to recite the Catechism of the Anglican Church. The results were amazingly successful. By 1740, 150 schools had been established, with 8,767 pupils by 1761, the year of Griffith Jones’ death, the Welch Piety recorded that 3,495 schools had been founded and 158,237 pupils taught in them.

After his death, Madam Bridget Bevan (1698 – 1779), who had been his major sponsor during his lifetime, continued with the work.

One of Griffith Jones’ schools was established at Capel Peulin and continued there during Madam Bevan’s time. She was the wife of Arthur Bevan, the Member of Parliament for Carmarthen from 1727 to 1744. On her death in 1779 she bequeathed £10,000 in order to form a trust to maintain the schools, but because of a dispute about the will by two of her trustees, her nephew, Vice-admiral William Lloyd of Danyrallt, Llangadog and her niece Lady Elizabeth Stepney of Llanelli, the bequest was put into Chancery, where it gathered interest for 30 years until it reached a total of more than £30,000. By then the schools had long closed because of lack of funds.

But in 1809 a scheme was devised to make use of the money by establishing Welsh Circulating schools in which reading, writing and arithmetic were taught. They were called, ‘Madam Bevan’s Charity Schools’. When the scheme came to an end in 1854, there were nine schools left in Carmarthenshire, namely, Eglwysfair Glantaf, Llandeilo, Llanelli, Llanfihangel-rhos-y-corn, Llangain, Llanllawddog, Llanllwch, St Clears and Ystradffin. The Capel Peulin School, Ystradffin was therefore, one of nine schools which succeeded in keeping its doors open to the end; they were not open however throughout the period from 1809 to 1854. Samuel Lewis in 1833 (in A Topographical Dictionary of Wales) says: ‘RHANDIR ABBOT….. The chapel of Nant y Bai is in this hamlet, having been re-erected here instead of at Ystrad-Ffin, where the original building stood. The living is a perpetual curacy, endowed with £200 private benefaction and £1,000 royal bounty, and in the patronage of Earl Cawdor. Here is a day school, containing 25 children, which is supported partly by Earl Cawdor, who allows the teacher £5 p.a. and partly by the parents; 3 Sunday Schools in which about 120 males and females are gratuitously taught’.

According to a statistical report on the Census of 1841, a schoolmaster, John Williams, lived in the first of eight houses in Nantybai. This school in Nantybai Chapel was certainly nearer to the majority of the population of the area than was the school in Ystradffin Chapel.

Both churches, Ystradffin and Nant-y-Bai were dedicated to Paulinus. Only three churches in Wales were dedicated to him, the third being Llanbeulin at Llangors, Breconshire. Capel Peulin, Ystradffin was re-built in 1821 and a monthly service is still held there. Capel Peulin, Nant-y-Bai is now in ruins although some local residents remember a house near Nant-y-Bai called the ‘meeting house’ and that Dai Tŷ Cwrdd was the last to live there.

The Sunday School Society was founded in London in 1785. This Society together with the excellent work of a pioneer in this field, Robert Raikes (1736 – 1811) was an inspiration to the movement in Wales. At the forefront of the movement in Wales was Thomas Jones of Bala and under his leadership the schools developed rapidly.

The great advantage of the Sunday School was the very fact that it was held on Sunday and was free of charge, and also that it was open to young and old, to men and women.

The early Sunday Schools were held in chapels and churches, barns and farmhouses and even in taverns or any other house where there was room for people to assemble. Children and adults were taught to read and often to write also, with the Bible being used as a textbook. The standard of instruction varied according to the teacher’s ability and training. The class usually lasted from an hour to two hours.

There was clearly a desire for such instruction in Rhandir-mwyn, considering the large numbers who attended Sunday School. The School certainly succeeded in conferring literacy on many who were previously illiterate and transformed the shy, reticent countryman into a confident speaker who could express himself fluently in his native language. This resulted from the reading, choral speaking and enthusiastic argument on religious and theological topics which occurred in the classes. At a time when the day schools ignored the Welsh language, the use made of it in Sunday School was certainly of very great importance in safeguarding its future.

The National School ^Top^

Early in the nineteenth century two national societies were formed in order to advance the cause of establishing primary schools throughout the country. For the next seven years these societies were to be prominent in the education sphere in Wales. Although their objectives were similar in the matter of the content of the curriculum and in religious education, there was a doctrinal gulf between them. The schools under the wing of The British and Foreign Schools Society were non-denominational and non-doctrinal, while those belonging to the National Society were Anglican in their modes of procedure and instruction.

Schools had already been established at the beginning of the century by people such as Joseph Lancaster (1778 – 1838), who believed that education should be available to all members of the community and that it should be non-doctrinal and non-denominational. The first of his schools in Wales was opened in Swansea in 1808. A number of prominent Quakers supported and financed such schools, among them Peter Price, a Quaker who was one of the ironmasters who founded the school at Neath Abbey for the poor children of the neighbourhood. Similar schools were also established at Brecon, Tremadoc, Abergavenny and Machen. The responsibility for maintaining these schools was transferred to The British and Foreign Schools Society, formally established in 1814. There was a small increase in the number of schools opened between 1814 and 1832. A small fee was charged at some schools – a halfpenny or a penny a day – in others a fee of a penny a week. Even so, the children of the poor usually received their education free of charge.

The growth of Nonconformity and the increasing number of nondenominational British Schools (as those of the British and Foreign Schools Society were called) was a source of some anxiety to the Established Church and the year 1811 saw the foundation of the National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church. Its ambitious aim was to establish a school in every parish in Wales and England at which the poor would receive instruction in the principles of the Established Church. Behind this purpose lay the strong desire to oppose the growing influence of nonconformists, who were seen as a threat to the Church. This Society’s schools were called National Schools.

The first National School in Wales was at Penley, in the Maelor district of Clwyd – a school adopted by the National Society in 1812. In 1815 National Schools were founded in Dyfed (Carmarthenshire and Ceredigion and Pembrokeshire) at Cardigan, Llandovery and Pembroke. Often these schools had previously been Church schools and had joined under the wing of the National Society.

The Rhandirmwyn National School opened its doors in 1860, but it was 1863 before the first minute appeared in the school’s first log book, which includes records for the years from 1863 to 1897. It opens with this note:

Rhandirmwyn National School

The above School was established in the year 1859 by the influence and efforts of the Revd. Joshua Hughes, Llandovery.

It was first opened on the 7th day of February 1860 under the care of James Thomas as its Principal Teacher and Thomas Evans, Pupil Teacher, who entered on his apprenticeship on 1st April 1860.’

This first head teacher was principal of the school until he resigned on January 29, 1864 and it is obvious he decided to join the ministry, since the following entry appears in the log book on March 31, 1869:

‘Revd. J Thomas, formerly a Master of the School, paid us a visit in the afternoon’.

The elements of reading, writing and arithmetic were taught to boys and girls in the National Schools and in many of them, including Rhandirmwyn, a monitorial system was in use, in which the best of the senior children took turns to drill the infants in those elements. Here are two entries in the logbook for 1866 which refers to the monitors:

‘July 4. The monitor reproved for neglecting his home lessons.’

It is obvious that a young girl also bore responsibility for the task, because later in the month the following entry is seen:

‘July 23. Monitor resigned her Office at 12 noon’.

National Schools were founded by Diocesan Committees and grants were made towards the school buildings by the National Society, but from then on it was the responsibility of the local committees to raise funds to maintain the school and pay teachers’ salaries. The usual practice was to charge a penny or two pence a week , without any charge for children whose parents could not afford to pay. No reference is made in the Rhandirmwyn school logbook to any children paying the penny or two pence, but they were expected to pay for coal to heat the school:

‘1865. March 1. A warning was today given to the children to bring money for fire to the School.’

‘1866. Jan 10. Told the children to bring money to get coal.’

The same arrangement was still in existence more than thirty years later, and by then had become a matter of dissension.

’16 Oct. 1899. The vicar (Rev. E. Morgan) called and asked the children to bring money for coal – 7d if only one child attends from a family, 6d each for two, and 5d each for more than two. The master refuses to receive the money so the Vicar told the Pupil Teacher, J. Thomas to take it.’

From time to time the children were expected not only pay for the coal but to carry it to school, as can be seen from the following entry for 1875. Since the school stood on a higher level than that of the roadway in front, it is clear that the horse and cart could not convey the load to the school yard at that time:

‘School not opened until 10.25 a.m. [the usual time was 9 a.m.] owing to the children assisting in carrying coal for the School into the yard.’

The main purpose of the National Schools was to provide moral guidance and religious instruction, but reading, writing, arithmetic and domestic science were also taught. The objective behind the establishment of many of these schools was to attract children into the Established Church and they were expected to attend the Church’s Sunday services as a condition of being accepted into school. This caused a good deal of anxiety to those parents who were Nonconformists and many sacrificed their beliefs in order to acquire formal education for their children. In a small, remote countryside village like Rhandirmwyn the parents were compelled to accept the education system as it was, and they had no other choice. The Church exerted a strong influence over the school throughout its existence, from the day it opened on February 7, 1860 until it closed more than a century later in December 1969. Regular visitors to the school in its early years were the Revd. Joshua Hughes of Llandovery and the curate:

‘1866 Jan. 15: Number present was 46. Revd. Joshua Hughes of Llandovery called this morning and heard all the children read.’

‘1866. Feb. 14: The Reverend Mr. Williams, the curate, called here this afternoon and examined the slates of the 1st. and 2nd. Classes who had been writing a part of the Catechism.’

‘1880 March 17: Mrs. Morgan, Vicarage, attended the Sewing this afternoon. The Revd. E. Morgan, took the Higher Standards in Reading and Grammar.’

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the authorities were greatly concerned about the problem of teaching monolingual Welsh children through the medium of a foreign language, English. The only means of advancement in the world was by mastering the English Language. The Welsh language was disregarded as being nothing more than a ‘native language’ by the Report of the Commissioners of Inquiry into the Rebecca Riots in 1843, and likewise reports of various Commissions relating to matters such as employment for women and children, land ownership, education and even the Established Church showed the same disrespect towards the Welsh and referred time and time again to the failure of the majority of the population to master the English language. This attitude towards the Welsh language was to continue until the present time. On the first page of the first Rhandirmwyn School logbook there appears a summary of the Inspector’s Report for the year 1863:

‘........the attainments of the Scholars are for the most part creditable considering the nature of the district and the few opportunities they have for hearing and becoming accustomed to English.’

Under the Revised Code of 1861, a year after the opening of Rhandirmwyn School the schools could take advantage of grants if they could attain certain standards. The amount of grant received depended on the children’s attendance and on their performance in an examination conducted annually by the School Inspector in English, reading, writing and arithmetic.

Certificates were awarded for regular attendance and a child was punished for absence. Receipt of a full grant depended on good results in the chosen subjects. Consequently, the children were drilled in those subjects, often to the total exclusion of others.

A summary of the report of the School Inspector dated June 12, 1867 in the logbook shows the effect which this Code had on a small rural school:

‘The attainment of the children in the School are below average. The Master is a tolerable fair teacher but he and the children must exert themselves more if they would have the School pass a creditable examination.

My Lords cannot sanction the issue of a certificate for Mr. Jones until they receive a better report on his School.

N.I. Williams

Secretary.’

But the report for 1887 end like this:

‘A very fair knowledge of English for a Welsh country school was shown.

Total Grant £50.7.0.’

One result of making the funding of the schools dependant upon those four subjects was to ensure that Welsh did not appear on the school curriculum. The teachers (many of them untrained) did not want to burden another language and every effort was made to get rid of it from within the walls of the school and from the yard. Various methods were used to prevent children from speaking Welsh, the best known being the use of the ‘Welsh Not’. This was a piece of wood with the letter ‘W.N.’ or the words ‘Welsh Not’ carved on it. Both ends were connected with a piece of rope and if a child was heard speaking Welsh within the area of the school, the piece of wood was put around his or her neck. If this child in turn heard another child speaking the language, he would transfer the wood to him or her. The pupil wearing this damnable piece of wood at the end of the day would be punished. There is no reference to this barbaric practice in the Rhandirmwyn logbooks, but on November 30, 1882 we find the following record:

‘Several boys were sent into School today during the dinner hour for speaking Welsh in the yard, it being general wish of the parents that the habit of speaking Welsh in School be stopped.’

The Curriculum ^Top^

In the Victorian years there is no mention of Welsh books in the Schools, nor of Welsh lessons, or lessons on any other subject through the medium of Welsh. There is no time-table of the subjects which were taught at that time but the logbooks do refer to the sort of subject-matter which used to be taught:

‘1869. Feb.22: William James and James Jones examined in Scripture, Grammer and Arithmetic.’

‘1869. Aug.26: William James commenced studying Geography from Cornwell’s Manual.’

‘1869. Sept. 1: William James commenced Book Keeping.’

‘1869. Nov. 18: Gave a lesson on Cube Root to William James and James Jones.’

‘1870. April. 21: Revd. J Jones questioned the 3rd. Class in the multiplication tables.’

‘1870. June. 10: The First Class wrote out the parable of the ‘Rich Fool’ on paper instead of copy-writing in the morning. Sewing and Singing in the afternoon.’

Here and there in the logbooks are lists of songs and recitations which had either been learned or were to be learned:

‘1879. March 24:

List of Songs

1. Catch the Sunshine

2. One true Heart

3. Men of Harlech

4. Birds are Singing

5. Try John

6. Lazy John

7. The Stately Homes of England

8. Winter Song

9. Summer Song

10. The Letters

11. The Tables

12. Come Away’

‘1882. Sept. 29: Taught a new song to the whole School – “Hearts of Oak”.’

‘1896. April 7: List of Recitation

Stds. I & II – A Mother’s Love

Stds. III & IV - The Battle of Blenheim

Stds. V, VI, VII – Legend of Horatius

Grammar Group I Stds. I & II: Pointing out Nouns and Verbs.

Grammar Group II Stds. III & IV: Pointing out the different parts of speech and parsing easy sentences etc.’

No mention is made of learning a Welsh air or of reciting any Welsh poetry. Nor do the minutes refer to the celebration of St David’s Day or a concert or play or Christmas held at the School in the Victorian age, apart from the following note:

‘1890. Jan. 27: Holiday. A tea-treat, kindly given by some ladies in the neighbourhood to the Schoolchildren. There was also a Magic Lantern Entertainment in the evening.’

This memorable occasion must have given the greatest pleasure to the children and was the topic of discussion among the local residents for weeks.

The logbooks of this period do not refer to the geography of Wales or to the history of the nation, nor is there any mention of local history or the geography of the area. Many members of today’s elder generation remember reciting together long lists of kings and queens of England, the capital cities of the countries of the world, the altitude of the world’s highest mountains and the length of the world’s longest rivers. The lives and works of local notables were completely ignored and no attention was paid to local studies, so that the pupils did not know the names of the rivers and streams which ran by the school or the hills which they saw from its windows. Nor is there any reference to the children and teachers venturing beyond the walls to study natural life – and this is one of the privileged schools located in an area of incomparable natural beauty, with a rich variety of wildlife and an open-air laboratory on the doorstep of the School.

But the era in which restricted education was being offered to unfortunate children in a foreign language by poorly-paid and untrained teachers was slowly coming to an end. The charge for attending school was abolished in 1891, causing the head teacher to note:

‘1891. Oct. 2: Free education being adopted there has been an increase in attendance.’

There was an improvement in the quality of the teachers, and according to the logbooks, John Hughes, who began his career as headmaster of Rhandirmwyn School on September 3 1895 was the first head teacher to hold a teaching certificate following a college course, and this thirty-five years after the opening of the School and forty-seven years since Trinity College, Carmarthen began training teachers 1n 1848.

Each headmaster who succeeded John Hughes possessed a certificate and the time came when every teacher on the staff of the School was required to hold a certificate and consequently to earn a respectable salary, so that no longer did one see a pitiable entry like this:

‘1899. March 15: John Thomas, pupil teacher, requested leave of absence at 3.15 p.m. to dig a grave; leave was granted.’

John Hughes therefore was the headmaster when Alice Harries of Erwrhwch (remembered by many villagers) first entered the infants’ school on April 14, 1896. Going to school for the first time on that day were Charles Renowdon and Lillian Robins. The following year, on November 17, 1897, there were 120 children on the School registers, the highest total recorded in its history. As a sign of general improvements seen at that time in education and in the history of Rhandirmwyn School in particular, we find the following entry:

‘1898. July 26:

Bessie Thomas, a pupil of the School, has won a Scholarship at the Llandovery Intermediate School, appearing 6th. On the list; also Thomas Theophilus gained a Scholarship at the Welsh Collegiate Institution, Llandovery, appearing 5th on the list.’

In this way a new and brighter age dawned in the history of Rhandirmwyn School, when children moved on to secondary education, a progression which was to lead to college and university education and a flourishing academic career for a number of pupils in years to come.

Attendance ^Top^

From 1892 to 1897 schools were funded according to their results (‘payment by results’). The amount of grant received was based on the children’s achievements in examinations in the three ‘Rs’ and also by their attendance. In the last year of this system the head teacher wrote the following note in the margin of the page which shows a summary of the School Inspector’s Report:

Principal Grant 12/6

Discipline & Organisation 1/6

Singing (ear) 6d

1st Class Subj. (Obj. Lesson & Eng.) 1/-

Total grant on 72 average = £55. 16. 0.

The average for the year was therefore 72 and it can be seen how the grant depended on this figure. We can also perhaps understand why it was that the head teachers were continually complaining about absences. Nevertheless, in rural areas there were calls upon the children to help on the farm with harvesting or sheep shearing, and the weather could effect the attendance. Time after time the logbooks contain entries such as:

‘1864. July 15: Attendance small today and all this week averaging from 30 to 40 on account of sheep shearing and hay harvest in the neighbourhood.’

‘1864. Sept. 22: Several children were absent this afternoon in consequence of a sale being held at Ystradffin.’

‘1864. Oct. 28: Children absent because of pay day in the village.’ ( It is obvious that the lead miners were paid at the end of the month.)

‘1864. Nov. 16: Absence today – fair at Llandovery.’

‘1867. March 14: Roads were stopped up with drifts of snow so that but 14 children were present.’

‘1867. April 12: Many of the children were kept at home to set the gardens.’

‘1867. Aug. 2: Attendance very low, there being a fair at Llandovery and a bidding in the neighbourhood.’ ( Bidding – Carmarthenshire tradition to announce a wedding.)

‘1869. April 26: Attendance very low. Many of the School children gone to work in the woods. Several also gone to Cynghordy station with their friends who are going away to America.’

‘1870. Aug. 24: Attendance very small owing to a Society at Salem to which several children belong.’

‘Summary of the Inspector’s Report on the School for 1871 (Revd. S. Pryce): The attendance at this School has decreased – the number present at inspection this year was 66. It is to be noted that the number of boys present was only 24. I was informed that they were sent at a very early age to work in the neighbouring lead mines.’

School attendance was made compulsory in 1880 but even so, parents still kept their children at home for many reasons. The head teacher had this to say on January 3, 1881:

‘I find that the Education Act as far as compulsory attendance is concerned is a dead letter in this parish.’

And on March 25, 1881, he declares:

‘There are several families with from three to five children of school age within easy distance who do not send a single child to school. It may be noticed that few children are admitted until they are between 8 and 9 years old.’

The next quotation from the logbook shows clearly that children of school age worked at the local lead mine:

‘1884. Sept. 29; re-admitted David Walters. Children can attend School or go ‘to work on the crusher’ at their own sweet will. The Attendance and Factory Acts have no terror for them.’

During the second half of the 19th Century, going to School must have been a miserable enough experience for the children. The incentives for good teachers were hardly any better. They were expected to teach children through the medium of a language many of them did not understand. Absences were frequent, the children’s progress was slow and their results in examinations poor. The school was not then qualified to receive the grant. It is, therefore, not surprising that there were frequent changes of head teachers – eight holding the post at Rhandirmwyn School in the first twenty years from 1860 – 1880.

If it appeared likely that many children would be absent because of some special occasion in the neighbourhood, the head teacher would close the school, this being preferable to showing the School Inspector a register with a very high level of absenteeism on that day:

‘1863. Aug. 17: No School today on account of the National Eisteddfod at Swansea; both Masters were down for the day only.’

‘1864. Oct. 5: School given up this afternoon, sale being at Gwernpwll. (local farm).

‘1866. Nov. 13: No School – fair at Cilycwm.’

‘1867. May 28: No School kept today, the Master and many of the children having gone to the

Eisteddfod which was held a little distance off at Cefngefel.’

‘1867. July 12: No School in consequence of monthly meetings being held at Salem.’

‘1867. Aug. 1: No School – Master gone to a lecture at Soar.’

On January 13, 1868 George Thomas Bright took charge of the School. He continued as headmaster until his retirement at 12 noon on July 30 in the same year. His successor had this to say on his first day:

‘1869. Jan. 11: Entered upon duties as Master of the Rhandirmwyn National school, John Davies, Master. I find that the School is in a very backward condition. A great number of children do not know the Alphabet. The Master has taken charge of the School under very unfavourable circumstances. The School has been closed about six months and its state was so bad at the last examinations that no Grant was obtained.’

‘1870. July 13: Holiday, owing to Mr. Campbell Davies Junior reaching his majority.’ (Campbell Davies were a wealthy family who resided in a country mansion called Neuadd Fawr, Cilycwm).

‘1871. Sept. 26: The first marriage was celebrated at St. Barnabas, so a holiday was given.’

‘1876. May 18: Great Meetings held at the Baptist Chapel.’

‘1897. June 22: Two days holiday was given to celebrate the Queen’s Jubilee.’

(Queen Victoria reigned from 1837 to 1901, so this holiday was to celebrate her diamond jubilee.)

Following the death of the Queen in 1901, Edward VII was crowned King and we find this brief record:

‘1902. June 24: Coronation – holiday.’

Of course holidays were not confined to great occasions of state, since there were dates on the farming calendar when holidays were taken:

‘1895. July 2: Holiday. Shearing at Ystradffin.

‘1902. July 11. Sheep-shearing holiday.’

Work on the farm accounted for much of the absence from school:

‘1894. Oct. 12: Attendance much smaller this week. Several children kept at home to assist in drawing potatoes.’

The logbook in recording children’s absences for agricultural reasons, shows the change in the use of the land, as in the following entry:

‘1892. Sept. 9: Corn harvest has commenced. Several children kept home.’

Some of the village residents remember wheat, oats and barley crops being grown generally on the neighbourhood’s farms in the early decades of the 20th century, resulting in plenty of work for the Nant-y-Bai mill where the miller, John Williams could be seen covered in flour from head to toe. There was enough local thatch to repair the local roofs, although there is no recollection of anyone pursuing a career as a thatcher, with the residents repairing their own roofs. By now very few can remember thatched roofs at the farms and houses except for the row of three houses at Nant-y-Bai and Troedrhiwfallen, Ty Cwrdd and Gorofmelyn cottages, all except the latter now in ruins. The smithy was also at Nant-y-Bai, where one could hear Jacob Hughes the blacksmith’s hammer tinkling on the anvil in the early years of the 20th century, since each farm had at least ‘two horses and a pony.’ It is not surprising that the busy lead mine, the farming activities, the social life of the district and events on a national scale influenced the school children’s level of attendance at the time.

Early Education - The National School - The Curriculum - Attendance - Rhandirmwyn School Head teachers

Early Education

Rhandirmwyn’s first school was held at Capel Peulin (St Paulinus’ Chapel), Ystradffin, owned in the Middle Ages by the Cistercians of Ystrad Fflur. The area was of special interest to the Cistercians because they owned the large Nant-y-Bai Farm (or ‘Nant Bey’ as was shown on the early maps of the Abbey Granges); this is also the location of Capel Peulin. Here Griffith Jones established one of his schools in a small, remote chapel in the middle of an area of remarkable natural beauty.

Griffith Jones (1683 – 1761) was a native of Penboyr, Carmarthenshire. He received his early education at Carmarthen Grammar School and was ordained in 1708. While serving as a curate at Laugharne he became a teacher at the SPCK School (the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge) and there he felt the desire to establish Welsh Circulating Schools. He moved to Llanddowror as a rector in 1716, remaining there for 25 years and henceforth became known as ‘Griffith Jones Llanddowror’. He was granted the rectorship by his friend and patron, Sir John Phillips and their friendship was further cemented when he married Sir John’s sister, Margaret in 1720.

Griffith Jones founded his first school in 1731, in Llanddowror in his native county. He then decided to establish more schools in the surrounding area. Teachers would serve for up to three months at one school before moving on to the next. In this way a large number of schools were founded by using a relatively small number of teachers. Usually in the winter months, the school would be held when there were less duties to be performed on the farms. Children and adults were taught to read the Scriptures in their native tongue and to recite the Catechism of the Anglican Church. The results were amazingly successful. By 1740, 150 schools had been established, with 8,767 pupils by 1761, the year of Griffith Jones’ death, the Welch Piety recorded that 3,495 schools had been founded and 158,237 pupils taught in them.

After his death, Madam Bridget Bevan (1698 – 1779), who had been his major sponsor during his lifetime, continued with the work.

One of Griffith Jones’ schools was established at Capel Peulin and continued there during Madam Bevan’s time. She was the wife of Arthur Bevan, the Member of Parliament for Carmarthen from 1727 to 1744. On her death in 1779 she bequeathed £10,000 in order to form a trust to maintain the schools, but because of a dispute about the will by two of her trustees, her nephew, Vice-admiral William Lloyd of Danyrallt, Llangadog and her niece Lady Elizabeth Stepney of Llanelli, the bequest was put into Chancery, where it gathered interest for 30 years until it reached a total of more than £30,000. By then the schools had long closed because of lack of funds.

But in 1809 a scheme was devised to make use of the money by establishing Welsh Circulating schools in which reading, writing and arithmetic were taught. They were called, ‘Madam Bevan’s Charity Schools’. When the scheme came to an end in 1854, there were nine schools left in Carmarthenshire, namely, Eglwysfair Glantaf, Llandeilo, Llanelli, Llanfihangel-rhos-y-corn, Llangain, Llanllawddog, Llanllwch, St Clears and Ystradffin. The Capel Peulin School, Ystradffin was therefore, one of nine schools which succeeded in keeping its doors open to the end; they were not open however throughout the period from 1809 to 1854. Samuel Lewis in 1833 (in A Topographical Dictionary of Wales) says: ‘RHANDIR ABBOT….. The chapel of Nant y Bai is in this hamlet, having been re-erected here instead of at Ystrad-Ffin, where the original building stood. The living is a perpetual curacy, endowed with £200 private benefaction and £1,000 royal bounty, and in the patronage of Earl Cawdor. Here is a day school, containing 25 children, which is supported partly by Earl Cawdor, who allows the teacher £5 p.a. and partly by the parents; 3 Sunday Schools in which about 120 males and females are gratuitously taught’.

According to a statistical report on the Census of 1841, a schoolmaster, John Williams, lived in the first of eight houses in Nantybai. This school in Nantybai Chapel was certainly nearer to the majority of the population of the area than was the school in Ystradffin Chapel.

Both churches, Ystradffin and Nant-y-Bai were dedicated to Paulinus. Only three churches in Wales were dedicated to him, the third being Llanbeulin at Llangors, Breconshire. Capel Peulin, Ystradffin was re-built in 1821 and a monthly service is still held there. Capel Peulin, Nant-y-Bai is now in ruins although some local residents remember a house near Nant-y-Bai called the ‘meeting house’ and that Dai Tŷ Cwrdd was the last to live there.

The Sunday School Society was founded in London in 1785. This Society together with the excellent work of a pioneer in this field, Robert Raikes (1736 – 1811) was an inspiration to the movement in Wales. At the forefront of the movement in Wales was Thomas Jones of Bala and under his leadership the schools developed rapidly.

The great advantage of the Sunday School was the very fact that it was held on Sunday and was free of charge, and also that it was open to young and old, to men and women.

The early Sunday Schools were held in chapels and churches, barns and farmhouses and even in taverns or any other house where there was room for people to assemble. Children and adults were taught to read and often to write also, with the Bible being used as a textbook. The standard of instruction varied according to the teacher’s ability and training. The class usually lasted from an hour to two hours.

There was clearly a desire for such instruction in Rhandir-mwyn, considering the large numbers who attended Sunday School. The School certainly succeeded in conferring literacy on many who were previously illiterate and transformed the shy, reticent countryman into a confident speaker who could express himself fluently in his native language. This resulted from the reading, choral speaking and enthusiastic argument on religious and theological topics which occurred in the classes. At a time when the day schools ignored the Welsh language, the use made of it in Sunday School was certainly of very great importance in safeguarding its future.

The National School ^Top^

Early in the nineteenth century two national societies were formed in order to advance the cause of establishing primary schools throughout the country. For the next seven years these societies were to be prominent in the education sphere in Wales. Although their objectives were similar in the matter of the content of the curriculum and in religious education, there was a doctrinal gulf between them. The schools under the wing of The British and Foreign Schools Society were non-denominational and non-doctrinal, while those belonging to the National Society were Anglican in their modes of procedure and instruction.

Schools had already been established at the beginning of the century by people such as Joseph Lancaster (1778 – 1838), who believed that education should be available to all members of the community and that it should be non-doctrinal and non-denominational. The first of his schools in Wales was opened in Swansea in 1808. A number of prominent Quakers supported and financed such schools, among them Peter Price, a Quaker who was one of the ironmasters who founded the school at Neath Abbey for the poor children of the neighbourhood. Similar schools were also established at Brecon, Tremadoc, Abergavenny and Machen. The responsibility for maintaining these schools was transferred to The British and Foreign Schools Society, formally established in 1814. There was a small increase in the number of schools opened between 1814 and 1832. A small fee was charged at some schools – a halfpenny or a penny a day – in others a fee of a penny a week. Even so, the children of the poor usually received their education free of charge.

The growth of Nonconformity and the increasing number of nondenominational British Schools (as those of the British and Foreign Schools Society were called) was a source of some anxiety to the Established Church and the year 1811 saw the foundation of the National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church. Its ambitious aim was to establish a school in every parish in Wales and England at which the poor would receive instruction in the principles of the Established Church. Behind this purpose lay the strong desire to oppose the growing influence of nonconformists, who were seen as a threat to the Church. This Society’s schools were called National Schools.

The first National School in Wales was at Penley, in the Maelor district of Clwyd – a school adopted by the National Society in 1812. In 1815 National Schools were founded in Dyfed (Carmarthenshire and Ceredigion and Pembrokeshire) at Cardigan, Llandovery and Pembroke. Often these schools had previously been Church schools and had joined under the wing of the National Society.

The Rhandirmwyn National School opened its doors in 1860, but it was 1863 before the first minute appeared in the school’s first log book, which includes records for the years from 1863 to 1897. It opens with this note:

Rhandirmwyn National School

The above School was established in the year 1859 by the influence and efforts of the Revd. Joshua Hughes, Llandovery.

It was first opened on the 7th day of February 1860 under the care of James Thomas as its Principal Teacher and Thomas Evans, Pupil Teacher, who entered on his apprenticeship on 1st April 1860.’

This first head teacher was principal of the school until he resigned on January 29, 1864 and it is obvious he decided to join the ministry, since the following entry appears in the log book on March 31, 1869:

‘Revd. J Thomas, formerly a Master of the School, paid us a visit in the afternoon’.

The elements of reading, writing and arithmetic were taught to boys and girls in the National Schools and in many of them, including Rhandirmwyn, a monitorial system was in use, in which the best of the senior children took turns to drill the infants in those elements. Here are two entries in the logbook for 1866 which refers to the monitors:

‘July 4. The monitor reproved for neglecting his home lessons.’

It is obvious that a young girl also bore responsibility for the task, because later in the month the following entry is seen:

‘July 23. Monitor resigned her Office at 12 noon’.

National Schools were founded by Diocesan Committees and grants were made towards the school buildings by the National Society, but from then on it was the responsibility of the local committees to raise funds to maintain the school and pay teachers’ salaries. The usual practice was to charge a penny or two pence a week , without any charge for children whose parents could not afford to pay. No reference is made in the Rhandirmwyn school logbook to any children paying the penny or two pence, but they were expected to pay for coal to heat the school:

‘1865. March 1. A warning was today given to the children to bring money for fire to the School.’

‘1866. Jan 10. Told the children to bring money to get coal.’

The same arrangement was still in existence more than thirty years later, and by then had become a matter of dissension.

’16 Oct. 1899. The vicar (Rev. E. Morgan) called and asked the children to bring money for coal – 7d if only one child attends from a family, 6d each for two, and 5d each for more than two. The master refuses to receive the money so the Vicar told the Pupil Teacher, J. Thomas to take it.’

From time to time the children were expected not only pay for the coal but to carry it to school, as can be seen from the following entry for 1875. Since the school stood on a higher level than that of the roadway in front, it is clear that the horse and cart could not convey the load to the school yard at that time:

‘School not opened until 10.25 a.m. [the usual time was 9 a.m.] owing to the children assisting in carrying coal for the School into the yard.’

The main purpose of the National Schools was to provide moral guidance and religious instruction, but reading, writing, arithmetic and domestic science were also taught. The objective behind the establishment of many of these schools was to attract children into the Established Church and they were expected to attend the Church’s Sunday services as a condition of being accepted into school. This caused a good deal of anxiety to those parents who were Nonconformists and many sacrificed their beliefs in order to acquire formal education for their children. In a small, remote countryside village like Rhandirmwyn the parents were compelled to accept the education system as it was, and they had no other choice. The Church exerted a strong influence over the school throughout its existence, from the day it opened on February 7, 1860 until it closed more than a century later in December 1969. Regular visitors to the school in its early years were the Revd. Joshua Hughes of Llandovery and the curate:

‘1866 Jan. 15: Number present was 46. Revd. Joshua Hughes of Llandovery called this morning and heard all the children read.’

‘1866. Feb. 14: The Reverend Mr. Williams, the curate, called here this afternoon and examined the slates of the 1st. and 2nd. Classes who had been writing a part of the Catechism.’

‘1880 March 17: Mrs. Morgan, Vicarage, attended the Sewing this afternoon. The Revd. E. Morgan, took the Higher Standards in Reading and Grammar.’

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the authorities were greatly concerned about the problem of teaching monolingual Welsh children through the medium of a foreign language, English. The only means of advancement in the world was by mastering the English Language. The Welsh language was disregarded as being nothing more than a ‘native language’ by the Report of the Commissioners of Inquiry into the Rebecca Riots in 1843, and likewise reports of various Commissions relating to matters such as employment for women and children, land ownership, education and even the Established Church showed the same disrespect towards the Welsh and referred time and time again to the failure of the majority of the population to master the English language. This attitude towards the Welsh language was to continue until the present time. On the first page of the first Rhandirmwyn School logbook there appears a summary of the Inspector’s Report for the year 1863:

‘........the attainments of the Scholars are for the most part creditable considering the nature of the district and the few opportunities they have for hearing and becoming accustomed to English.’

Under the Revised Code of 1861, a year after the opening of Rhandirmwyn School the schools could take advantage of grants if they could attain certain standards. The amount of grant received depended on the children’s attendance and on their performance in an examination conducted annually by the School Inspector in English, reading, writing and arithmetic.

Certificates were awarded for regular attendance and a child was punished for absence. Receipt of a full grant depended on good results in the chosen subjects. Consequently, the children were drilled in those subjects, often to the total exclusion of others.

A summary of the report of the School Inspector dated June 12, 1867 in the logbook shows the effect which this Code had on a small rural school:

‘The attainment of the children in the School are below average. The Master is a tolerable fair teacher but he and the children must exert themselves more if they would have the School pass a creditable examination.

My Lords cannot sanction the issue of a certificate for Mr. Jones until they receive a better report on his School.

N.I. Williams

Secretary.’

But the report for 1887 end like this:

‘A very fair knowledge of English for a Welsh country school was shown.

Total Grant £50.7.0.’

One result of making the funding of the schools dependant upon those four subjects was to ensure that Welsh did not appear on the school curriculum. The teachers (many of them untrained) did not want to burden another language and every effort was made to get rid of it from within the walls of the school and from the yard. Various methods were used to prevent children from speaking Welsh, the best known being the use of the ‘Welsh Not’. This was a piece of wood with the letter ‘W.N.’ or the words ‘Welsh Not’ carved on it. Both ends were connected with a piece of rope and if a child was heard speaking Welsh within the area of the school, the piece of wood was put around his or her neck. If this child in turn heard another child speaking the language, he would transfer the wood to him or her. The pupil wearing this damnable piece of wood at the end of the day would be punished. There is no reference to this barbaric practice in the Rhandirmwyn logbooks, but on November 30, 1882 we find the following record:

‘Several boys were sent into School today during the dinner hour for speaking Welsh in the yard, it being general wish of the parents that the habit of speaking Welsh in School be stopped.’

The Curriculum ^Top^

In the Victorian years there is no mention of Welsh books in the Schools, nor of Welsh lessons, or lessons on any other subject through the medium of Welsh. There is no time-table of the subjects which were taught at that time but the logbooks do refer to the sort of subject-matter which used to be taught:

‘1869. Feb.22: William James and James Jones examined in Scripture, Grammer and Arithmetic.’

‘1869. Aug.26: William James commenced studying Geography from Cornwell’s Manual.’

‘1869. Sept. 1: William James commenced Book Keeping.’

‘1869. Nov. 18: Gave a lesson on Cube Root to William James and James Jones.’

‘1870. April. 21: Revd. J Jones questioned the 3rd. Class in the multiplication tables.’

‘1870. June. 10: The First Class wrote out the parable of the ‘Rich Fool’ on paper instead of copy-writing in the morning. Sewing and Singing in the afternoon.’

Here and there in the logbooks are lists of songs and recitations which had either been learned or were to be learned:

‘1879. March 24:

List of Songs

1. Catch the Sunshine

2. One true Heart

3. Men of Harlech

4. Birds are Singing

5. Try John

6. Lazy John

7. The Stately Homes of England

8. Winter Song

9. Summer Song

10. The Letters

11. The Tables

12. Come Away’

‘1882. Sept. 29: Taught a new song to the whole School – “Hearts of Oak”.’

‘1896. April 7: List of Recitation

Stds. I & II – A Mother’s Love

Stds. III & IV - The Battle of Blenheim

Stds. V, VI, VII – Legend of Horatius

Grammar Group I Stds. I & II: Pointing out Nouns and Verbs.

Grammar Group II Stds. III & IV: Pointing out the different parts of speech and parsing easy sentences etc.’

No mention is made of learning a Welsh air or of reciting any Welsh poetry. Nor do the minutes refer to the celebration of St David’s Day or a concert or play or Christmas held at the School in the Victorian age, apart from the following note:

‘1890. Jan. 27: Holiday. A tea-treat, kindly given by some ladies in the neighbourhood to the Schoolchildren. There was also a Magic Lantern Entertainment in the evening.’

This memorable occasion must have given the greatest pleasure to the children and was the topic of discussion among the local residents for weeks.

The logbooks of this period do not refer to the geography of Wales or to the history of the nation, nor is there any mention of local history or the geography of the area. Many members of today’s elder generation remember reciting together long lists of kings and queens of England, the capital cities of the countries of the world, the altitude of the world’s highest mountains and the length of the world’s longest rivers. The lives and works of local notables were completely ignored and no attention was paid to local studies, so that the pupils did not know the names of the rivers and streams which ran by the school or the hills which they saw from its windows. Nor is there any reference to the children and teachers venturing beyond the walls to study natural life – and this is one of the privileged schools located in an area of incomparable natural beauty, with a rich variety of wildlife and an open-air laboratory on the doorstep of the School.

But the era in which restricted education was being offered to unfortunate children in a foreign language by poorly-paid and untrained teachers was slowly coming to an end. The charge for attending school was abolished in 1891, causing the head teacher to note:

‘1891. Oct. 2: Free education being adopted there has been an increase in attendance.’

There was an improvement in the quality of the teachers, and according to the logbooks, John Hughes, who began his career as headmaster of Rhandirmwyn School on September 3 1895 was the first head teacher to hold a teaching certificate following a college course, and this thirty-five years after the opening of the School and forty-seven years since Trinity College, Carmarthen began training teachers 1n 1848.

Each headmaster who succeeded John Hughes possessed a certificate and the time came when every teacher on the staff of the School was required to hold a certificate and consequently to earn a respectable salary, so that no longer did one see a pitiable entry like this:

‘1899. March 15: John Thomas, pupil teacher, requested leave of absence at 3.15 p.m. to dig a grave; leave was granted.’

John Hughes therefore was the headmaster when Alice Harries of Erwrhwch (remembered by many villagers) first entered the infants’ school on April 14, 1896. Going to school for the first time on that day were Charles Renowdon and Lillian Robins. The following year, on November 17, 1897, there were 120 children on the School registers, the highest total recorded in its history. As a sign of general improvements seen at that time in education and in the history of Rhandirmwyn School in particular, we find the following entry:

‘1898. July 26:

Bessie Thomas, a pupil of the School, has won a Scholarship at the Llandovery Intermediate School, appearing 6th. On the list; also Thomas Theophilus gained a Scholarship at the Welsh Collegiate Institution, Llandovery, appearing 5th on the list.’

In this way a new and brighter age dawned in the history of Rhandirmwyn School, when children moved on to secondary education, a progression which was to lead to college and university education and a flourishing academic career for a number of pupils in years to come.

Attendance ^Top^

From 1892 to 1897 schools were funded according to their results (‘payment by results’). The amount of grant received was based on the children’s achievements in examinations in the three ‘Rs’ and also by their attendance. In the last year of this system the head teacher wrote the following note in the margin of the page which shows a summary of the School Inspector’s Report:

Principal Grant 12/6

Discipline & Organisation 1/6

Singing (ear) 6d

1st Class Subj. (Obj. Lesson & Eng.) 1/-

Total grant on 72 average = £55. 16. 0.

The average for the year was therefore 72 and it can be seen how the grant depended on this figure. We can also perhaps understand why it was that the head teachers were continually complaining about absences. Nevertheless, in rural areas there were calls upon the children to help on the farm with harvesting or sheep shearing, and the weather could effect the attendance. Time after time the logbooks contain entries such as:

‘1864. July 15: Attendance small today and all this week averaging from 30 to 40 on account of sheep shearing and hay harvest in the neighbourhood.’

‘1864. Sept. 22: Several children were absent this afternoon in consequence of a sale being held at Ystradffin.’

‘1864. Oct. 28: Children absent because of pay day in the village.’ ( It is obvious that the lead miners were paid at the end of the month.)

‘1864. Nov. 16: Absence today – fair at Llandovery.’

‘1867. March 14: Roads were stopped up with drifts of snow so that but 14 children were present.’

‘1867. April 12: Many of the children were kept at home to set the gardens.’

‘1867. Aug. 2: Attendance very low, there being a fair at Llandovery and a bidding in the neighbourhood.’ ( Bidding – Carmarthenshire tradition to announce a wedding.)

‘1869. April 26: Attendance very low. Many of the School children gone to work in the woods. Several also gone to Cynghordy station with their friends who are going away to America.’

‘1870. Aug. 24: Attendance very small owing to a Society at Salem to which several children belong.’

‘Summary of the Inspector’s Report on the School for 1871 (Revd. S. Pryce): The attendance at this School has decreased – the number present at inspection this year was 66. It is to be noted that the number of boys present was only 24. I was informed that they were sent at a very early age to work in the neighbouring lead mines.’

School attendance was made compulsory in 1880 but even so, parents still kept their children at home for many reasons. The head teacher had this to say on January 3, 1881:

‘I find that the Education Act as far as compulsory attendance is concerned is a dead letter in this parish.’

And on March 25, 1881, he declares:

‘There are several families with from three to five children of school age within easy distance who do not send a single child to school. It may be noticed that few children are admitted until they are between 8 and 9 years old.’

The next quotation from the logbook shows clearly that children of school age worked at the local lead mine:

‘1884. Sept. 29; re-admitted David Walters. Children can attend School or go ‘to work on the crusher’ at their own sweet will. The Attendance and Factory Acts have no terror for them.’

During the second half of the 19th Century, going to School must have been a miserable enough experience for the children. The incentives for good teachers were hardly any better. They were expected to teach children through the medium of a language many of them did not understand. Absences were frequent, the children’s progress was slow and their results in examinations poor. The school was not then qualified to receive the grant. It is, therefore, not surprising that there were frequent changes of head teachers – eight holding the post at Rhandirmwyn School in the first twenty years from 1860 – 1880.

If it appeared likely that many children would be absent because of some special occasion in the neighbourhood, the head teacher would close the school, this being preferable to showing the School Inspector a register with a very high level of absenteeism on that day:

‘1863. Aug. 17: No School today on account of the National Eisteddfod at Swansea; both Masters were down for the day only.’

‘1864. Oct. 5: School given up this afternoon, sale being at Gwernpwll. (local farm).

‘1866. Nov. 13: No School – fair at Cilycwm.’

‘1867. May 28: No School kept today, the Master and many of the children having gone to the

Eisteddfod which was held a little distance off at Cefngefel.’

‘1867. July 12: No School in consequence of monthly meetings being held at Salem.’

‘1867. Aug. 1: No School – Master gone to a lecture at Soar.’

On January 13, 1868 George Thomas Bright took charge of the School. He continued as headmaster until his retirement at 12 noon on July 30 in the same year. His successor had this to say on his first day:

‘1869. Jan. 11: Entered upon duties as Master of the Rhandirmwyn National school, John Davies, Master. I find that the School is in a very backward condition. A great number of children do not know the Alphabet. The Master has taken charge of the School under very unfavourable circumstances. The School has been closed about six months and its state was so bad at the last examinations that no Grant was obtained.’

‘1870. July 13: Holiday, owing to Mr. Campbell Davies Junior reaching his majority.’ (Campbell Davies were a wealthy family who resided in a country mansion called Neuadd Fawr, Cilycwm).

‘1871. Sept. 26: The first marriage was celebrated at St. Barnabas, so a holiday was given.’

‘1876. May 18: Great Meetings held at the Baptist Chapel.’

‘1897. June 22: Two days holiday was given to celebrate the Queen’s Jubilee.’

(Queen Victoria reigned from 1837 to 1901, so this holiday was to celebrate her diamond jubilee.)

Following the death of the Queen in 1901, Edward VII was crowned King and we find this brief record:

‘1902. June 24: Coronation – holiday.’

Of course holidays were not confined to great occasions of state, since there were dates on the farming calendar when holidays were taken:

‘1895. July 2: Holiday. Shearing at Ystradffin.

‘1902. July 11. Sheep-shearing holiday.’

Work on the farm accounted for much of the absence from school:

‘1894. Oct. 12: Attendance much smaller this week. Several children kept at home to assist in drawing potatoes.’

The logbook in recording children’s absences for agricultural reasons, shows the change in the use of the land, as in the following entry:

‘1892. Sept. 9: Corn harvest has commenced. Several children kept home.’

Some of the village residents remember wheat, oats and barley crops being grown generally on the neighbourhood’s farms in the early decades of the 20th century, resulting in plenty of work for the Nant-y-Bai mill where the miller, John Williams could be seen covered in flour from head to toe. There was enough local thatch to repair the local roofs, although there is no recollection of anyone pursuing a career as a thatcher, with the residents repairing their own roofs. By now very few can remember thatched roofs at the farms and houses except for the row of three houses at Nant-y-Bai and Troedrhiwfallen, Ty Cwrdd and Gorofmelyn cottages, all except the latter now in ruins. The smithy was also at Nant-y-Bai, where one could hear Jacob Hughes the blacksmith’s hammer tinkling on the anvil in the early years of the 20th century, since each farm had at least ‘two horses and a pony.’ It is not surprising that the busy lead mine, the farming activities, the social life of the district and events on a national scale influenced the school children’s level of attendance at the time.

Head Masters

Rhandirmwyn School Head teachers

The school opened on February 7, 1860 and closed on December 19, 1969.

February 1860 - January 1864 James Thomas

February 1864 - December 1865 Owen Evans

January 1866 - December 1867 Thomas Jones

January 1868 - July 1868 George Thomas Bright

January 1869 - February 1870 John Davies

February 1870 - March 1871 Elizabeth Anne Williams

April 1871 - August 1878 Anne George

August 1878 - July 1880 Hugh Solomon Williams

August 1880 - December 1885 Thomas Jones

January 1886 - August 1895 David Owen

September 1895 - July 1898 John Hughes

January 1899 - October 1900 Edgar John Stanbury

November 1900 - August 1902 Thomas Owen

October 1902 - November 1903 John T. Jones

November 1903 - July 1904 Ebenezer Davies

September 1904 - August 1922 David Vincent Lewis

October 1922 - October 1930 Isaac William Thomas

November 1930 - April 1950 W. Brynmor Jones

April 1950 - December 1957 P. Vernon Griffiths

January 1958 - December 1969 David Davies.

The school opened on February 7, 1860 and closed on December 19, 1969.

February 1860 - January 1864 James Thomas

February 1864 - December 1865 Owen Evans

January 1866 - December 1867 Thomas Jones

January 1868 - July 1868 George Thomas Bright

January 1869 - February 1870 John Davies

February 1870 - March 1871 Elizabeth Anne Williams

April 1871 - August 1878 Anne George

August 1878 - July 1880 Hugh Solomon Williams

August 1880 - December 1885 Thomas Jones

January 1886 - August 1895 David Owen

September 1895 - July 1898 John Hughes

January 1899 - October 1900 Edgar John Stanbury

November 1900 - August 1902 Thomas Owen

October 1902 - November 1903 John T. Jones

November 1903 - July 1904 Ebenezer Davies

September 1904 - August 1922 David Vincent Lewis

October 1922 - October 1930 Isaac William Thomas

November 1930 - April 1950 W. Brynmor Jones

April 1950 - December 1957 P. Vernon Griffiths

January 1958 - December 1969 David Davies.

Rhandirmwyn - Old School - Evacuees 1940

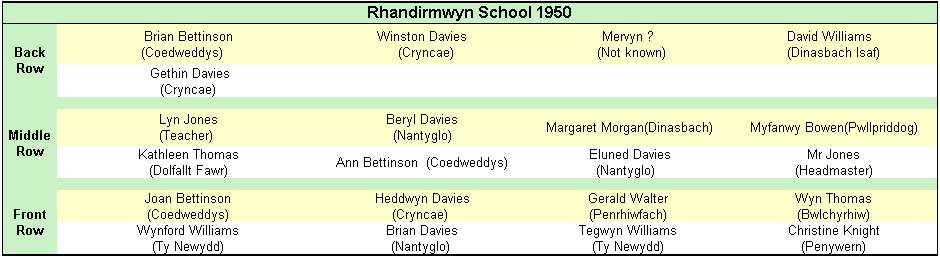

1950

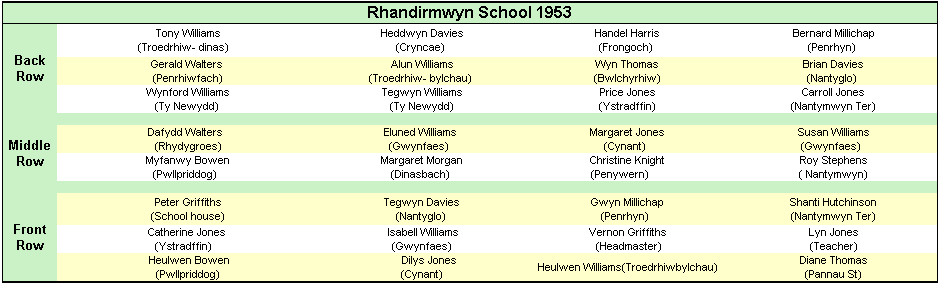

1953

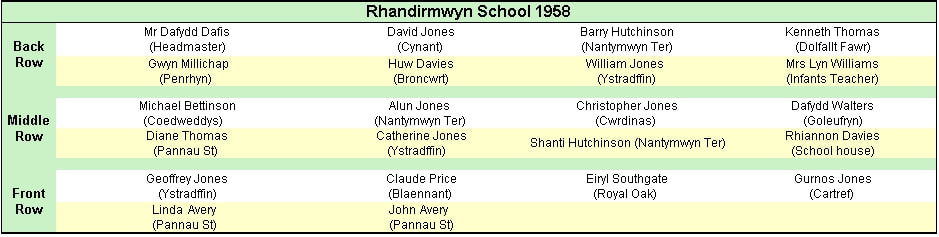

1958

School Magazine

Here you will see three copies of the school magazine. 1959, 1960 and 1961.

My late mother who was a wonderful hoarder had kept them in an old box and It was wonderful to read through them again. It was therefor felt suitable that they be included on the website. Sadly some of the print has become very faint so we have made fresh copies but have also included the originals. Mr Davies the headmaster raised money through various events to buy a Gestetner duplicating machine and later a Bar-lock typewriter and hence copies of the magazine were produced.

I am not certain how many years the magazine was in production but if there are any others out there then please let me know.

Alun Jones

Download

School Magazine 1959

School Magazine 1960 - 1960 -1-

School Magazine 1961 - 1961-1

My late mother who was a wonderful hoarder had kept them in an old box and It was wonderful to read through them again. It was therefor felt suitable that they be included on the website. Sadly some of the print has become very faint so we have made fresh copies but have also included the originals. Mr Davies the headmaster raised money through various events to buy a Gestetner duplicating machine and later a Bar-lock typewriter and hence copies of the magazine were produced.

I am not certain how many years the magazine was in production but if there are any others out there then please let me know.

Alun Jones

Download

School Magazine 1959

School Magazine 1960 - 1960 -1-

School Magazine 1961 - 1961-1