Dafydd Dafis

Dafydd Dafis was born on 29th September 1924 in the mining village of Cwmgiedd in the Swansea Valley.

After leaving school in 1943 he joined the RAF and saw service in Canada and Great Britain. He was de-mobbed in 1947.

In September 1947 he entered Trinity College, Carmarthen, to be trained as a teacher. At the end of the course, he went to teach at Holloway Head Secondary Modern School, Birmingham.

He later applied for the post of Rural Science master at Llandrindod County Secondary School. After 3 years at Llandrindod he applied for ‘the post of headmaster of Rhandirmwyn School and transferred there a few days before Christmas 1957.

He says………

The next 25 years or so were to be a rural idyll. We lived in the school-house and came to enjoy life in a community that was almost entirely Welsh-speaking. The children I taught were the sons and daughters of farmers and foresters mainly’.

I Served also on the Committee for Wales of The Forestry Commission, chaired by Mr. Gibson-Watt. With the approval of the NCC and the FC I set up a nature reserve for the school at Allt yr Hwch, a high altitude oak wood on Forestry Commission Land.

In 1968 I was admitted a Fellow of the Linnean Society of London. The end of the following year saw the closure of Rhandirmwyn School despite the efforts of the County Council to keep it open; the numbers in the end had fallen to just three children. A period of teaching at Llandovery County Secondary School followed before I took up headship duties at Capel Cynfab Primary School in neighboring Cynghordy village, where I spent the next 14 years before my retirement.

On the 8 August 1991 I was admitted as Ovate to the Gorsedd of Bards during

the National Eisteddfod of Wales held at Mold, an honour which I greatly esteem.

In July 1992 I was awarded the honorary degree of MSc. by the University of Wales in a ceremony held at Cardiff University’.

After leaving school in 1943 he joined the RAF and saw service in Canada and Great Britain. He was de-mobbed in 1947.

In September 1947 he entered Trinity College, Carmarthen, to be trained as a teacher. At the end of the course, he went to teach at Holloway Head Secondary Modern School, Birmingham.

He later applied for the post of Rural Science master at Llandrindod County Secondary School. After 3 years at Llandrindod he applied for ‘the post of headmaster of Rhandirmwyn School and transferred there a few days before Christmas 1957.

He says………

The next 25 years or so were to be a rural idyll. We lived in the school-house and came to enjoy life in a community that was almost entirely Welsh-speaking. The children I taught were the sons and daughters of farmers and foresters mainly’.

I Served also on the Committee for Wales of The Forestry Commission, chaired by Mr. Gibson-Watt. With the approval of the NCC and the FC I set up a nature reserve for the school at Allt yr Hwch, a high altitude oak wood on Forestry Commission Land.

In 1968 I was admitted a Fellow of the Linnean Society of London. The end of the following year saw the closure of Rhandirmwyn School despite the efforts of the County Council to keep it open; the numbers in the end had fallen to just three children. A period of teaching at Llandovery County Secondary School followed before I took up headship duties at Capel Cynfab Primary School in neighboring Cynghordy village, where I spent the next 14 years before my retirement.

On the 8 August 1991 I was admitted as Ovate to the Gorsedd of Bards during

the National Eisteddfod of Wales held at Mold, an honour which I greatly esteem.

In July 1992 I was awarded the honorary degree of MSc. by the University of Wales in a ceremony held at Cardiff University’.

The Old Lead Mine By Dafydd Dafis.

Considering the natural beauty of the area and its agricultural character, visitors to Rhandirmwyn find it difficult to believe that it was a thriving, industrial village up to the 1930’s. Fortunately, most of the ugly remains of that industry are hidden behind wooded hills and heather-clad slopes in an unfrequented spot, where the only sounds heard today are the bleating of sheep and the crowing of the raven. Consequently, the great majority of the thousands who visit Llyn Brianne reservoir every summer are not conscious of the industrial background to the village’s history. (Llyn Brianne dam was built, using waste from the Nantymwyn lead mine).

Most of the old lead mine is situated in the valley of Nant-y-bai, a stream with its source at Cefn-Ystradffin, and flowing in a south-westerly direction to join with the Tywi about half-way between the Pwllpriddog and Broncwrt (Towy) bridges. Yet the name given to the works was Nantymwyn, a stream rising at Pencerrig-mwyn and running through the middle of the village, and it is true that there were some shafts and levels on the slopes above the village and near to the houses.

A substantial amount of metalliferous, non-ferrous ores were dug from the Silurian and Ordovician rocks of Mid-Wales from Roman times to the early years of this century, and according to G. W. Hall (1971), Nantymwyn was the most important metal mine in South Wales except for Ogofau at Pumsaint, because of the quantity of lead ore obtained there.

The most common ores in the mid-region are lead sulphide (galena, PbS) and zinc (sphalerite, ZnS). But along with them is a smaller quantity of silver and copper ores. For a long period in the history of the works in the region, including Nantymwyn, only silver and lead were extracted, the zinc being ignored until the demand for galvanised iron increased in 1850.

It is likely that the first vein to be discovered and worked was the Old Vein, which rises near the top of Pencerrig-mwyn (map ref. SN 790 444) about 1250 feet above sea level. According to John Rolley’s map drawn before 1800, it is said that the Romans discovered this vein, but there is no knowledge of any support for this claim. The landowner, Lord Cawdor, ran the works at this time and Rolley was his estate manager at Rhandirmwyn. Bearing in mind the complexity of excavations and tunnels found on maps of this period, it is highly likely that mining for ores had happened here for a long before the maps were prepared. The name given to the mine at this time was Cerrig-mwyn and a watercolour painting by John Warwick Smith dated 1792 and housed at the National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth shows a picture of the mine with a water-wheel at the entrance to the Upper Boat Level.

It is known that the works flourished between 1775 and 1823. The accounts for the years from 1775 to 1797 (among the Cawdor Papers at the Carmarthenshire Archive Service) give the figures for the ore extracted annually during this period and the annual profit. Running costs for this period totalled £126,000, the workers employed were up to 400 and 30,000 tons of ore was raised. The profits varied from £12,526.13s.11d. in 1779 to £320. 12s 6d. in 1797. During the 23 years in question the annual profit was on average £3,770 which brought great riches to Lord Cawdor.

John Rolley died in 1805 and was succeeded by Cornishman, Joel Williams. Although circumstances were more difficult because of a decrease in the ore which was mined, between 300 and 500 tons a year were produced during his tenure in office. But in 1923, it appears that Williams was dismissed and soon afterwards Lord Cawdor decided that, because the mine was not making the profit he was used to, he would call it a day and lease the works. Various companies then took over until in 1836 it came into the hands of Messrs Williams of Scorrier House, near Redruth and they held the lease until 1900.

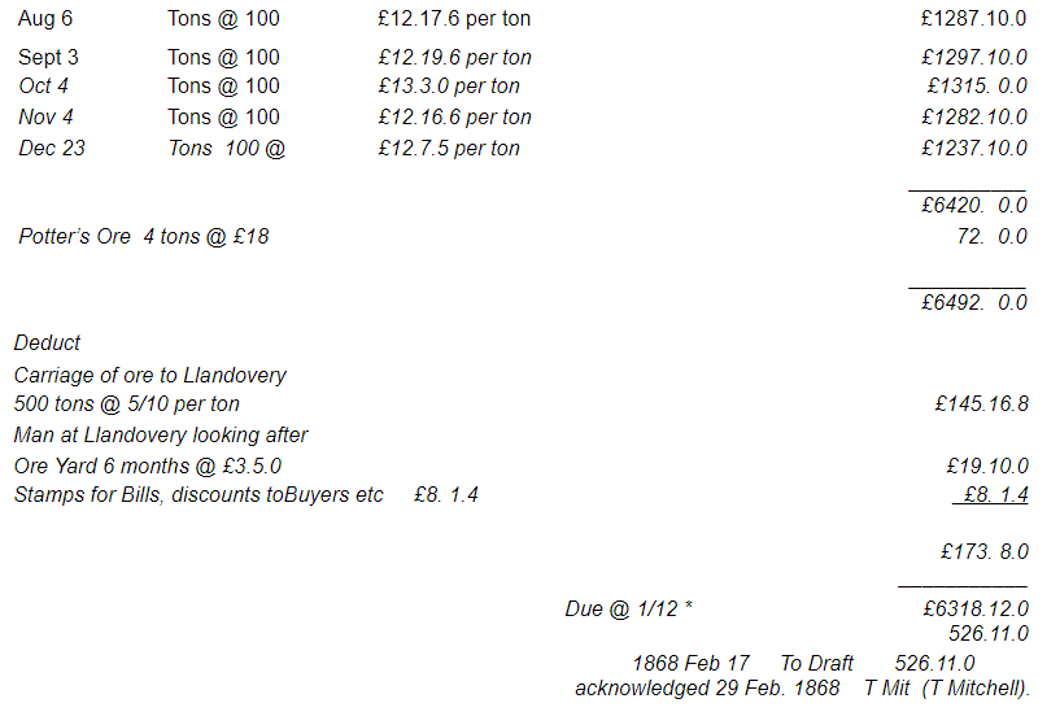

Among the Cawdor Papers is the following credit note relating to the payment due to the Earl for the period of six months ending on the last day of December 1867

Most of the old lead mine is situated in the valley of Nant-y-bai, a stream with its source at Cefn-Ystradffin, and flowing in a south-westerly direction to join with the Tywi about half-way between the Pwllpriddog and Broncwrt (Towy) bridges. Yet the name given to the works was Nantymwyn, a stream rising at Pencerrig-mwyn and running through the middle of the village, and it is true that there were some shafts and levels on the slopes above the village and near to the houses.

A substantial amount of metalliferous, non-ferrous ores were dug from the Silurian and Ordovician rocks of Mid-Wales from Roman times to the early years of this century, and according to G. W. Hall (1971), Nantymwyn was the most important metal mine in South Wales except for Ogofau at Pumsaint, because of the quantity of lead ore obtained there.

The most common ores in the mid-region are lead sulphide (galena, PbS) and zinc (sphalerite, ZnS). But along with them is a smaller quantity of silver and copper ores. For a long period in the history of the works in the region, including Nantymwyn, only silver and lead were extracted, the zinc being ignored until the demand for galvanised iron increased in 1850.

It is likely that the first vein to be discovered and worked was the Old Vein, which rises near the top of Pencerrig-mwyn (map ref. SN 790 444) about 1250 feet above sea level. According to John Rolley’s map drawn before 1800, it is said that the Romans discovered this vein, but there is no knowledge of any support for this claim. The landowner, Lord Cawdor, ran the works at this time and Rolley was his estate manager at Rhandirmwyn. Bearing in mind the complexity of excavations and tunnels found on maps of this period, it is highly likely that mining for ores had happened here for a long before the maps were prepared. The name given to the mine at this time was Cerrig-mwyn and a watercolour painting by John Warwick Smith dated 1792 and housed at the National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth shows a picture of the mine with a water-wheel at the entrance to the Upper Boat Level.

It is known that the works flourished between 1775 and 1823. The accounts for the years from 1775 to 1797 (among the Cawdor Papers at the Carmarthenshire Archive Service) give the figures for the ore extracted annually during this period and the annual profit. Running costs for this period totalled £126,000, the workers employed were up to 400 and 30,000 tons of ore was raised. The profits varied from £12,526.13s.11d. in 1779 to £320. 12s 6d. in 1797. During the 23 years in question the annual profit was on average £3,770 which brought great riches to Lord Cawdor.

John Rolley died in 1805 and was succeeded by Cornishman, Joel Williams. Although circumstances were more difficult because of a decrease in the ore which was mined, between 300 and 500 tons a year were produced during his tenure in office. But in 1923, it appears that Williams was dismissed and soon afterwards Lord Cawdor decided that, because the mine was not making the profit he was used to, he would call it a day and lease the works. Various companies then took over until in 1836 it came into the hands of Messrs Williams of Scorrier House, near Redruth and they held the lease until 1900.

Among the Cawdor Papers is the following credit note relating to the payment due to the Earl for the period of six months ending on the last day of December 1867

Cr. Earl Cawdor for Lead and Lead Ore

Dues sold 6 months to end December 1867

Dues sold 6 months to end December 1867

1967

One twelfth of the price of ore, after deducting the cost of its carriage to Llandovery and other minor charges, was to be paid to the Earl of Cawdor and came to the sum of £526 for the six-month period, - £206 more than the profit which he made for the whole of 1797. The estate therefore gained an advantage by leasing the work.

As can be seen, the payment for carrying 500 tons of the ore at 5/10 (29 pence) per ton was £145. 16s 8d (£145.83). It was transported to Llandovery along poor roads by local farmers using horse and cart, and it is certain that the payment would have been very welcome as a supplement to their income in those times. Daily records were kept of the carters, their names, the name of the farm and the weight of the mineral carried.

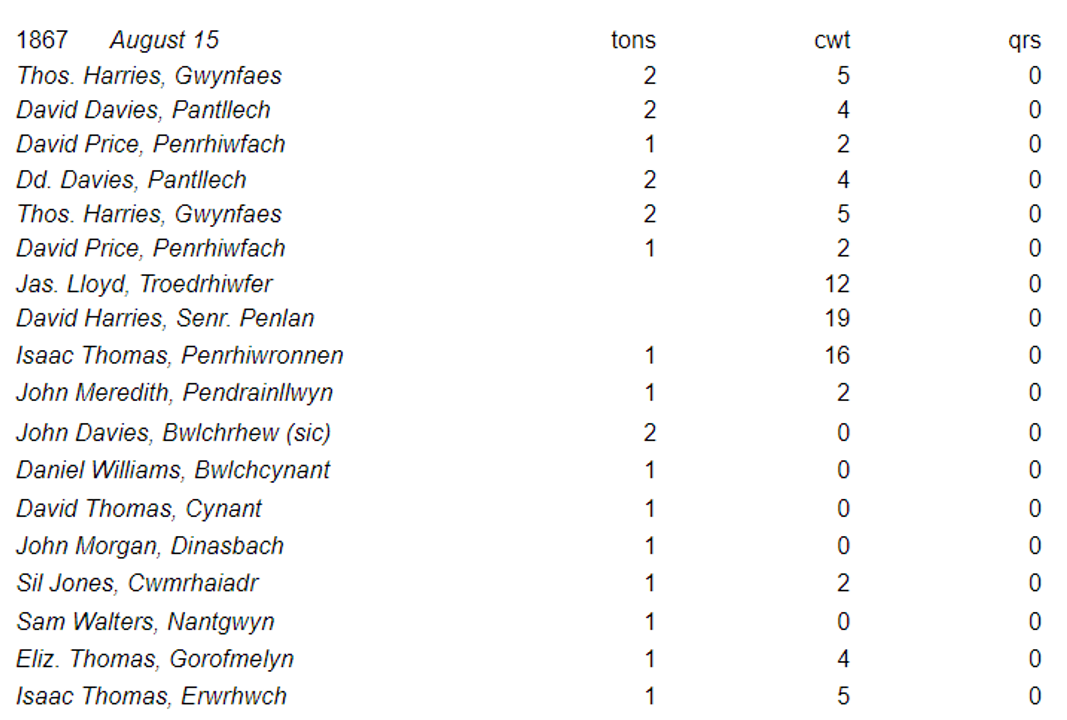

Everything was noted in excellent handwriting in thick volumes with sturdy binding. These volumes are still available at the Carmarthenshire Archive Service and since the credit note relates to the period from August to December 1867, I chose a day in August 1867 – the 15th of the month – as an example-

As can be seen, the payment for carrying 500 tons of the ore at 5/10 (29 pence) per ton was £145. 16s 8d (£145.83). It was transported to Llandovery along poor roads by local farmers using horse and cart, and it is certain that the payment would have been very welcome as a supplement to their income in those times. Daily records were kept of the carters, their names, the name of the farm and the weight of the mineral carried.

Everything was noted in excellent handwriting in thick volumes with sturdy binding. These volumes are still available at the Carmarthenshire Archive Service and since the credit note relates to the period from August to December 1867, I chose a day in August 1867 – the 15th of the month – as an example-

Carriage of Lead Ore

So 18 loads of lead ore were carried on that day, totalling 26 tons 2 hundredweight and no quarters, from Nant-y-bai to Llandovery. For the two loads which he conveyed Thos. Harries, Gwynfaes would have earned:

t c q

04 10 0 @ 5/10 per ton = £1. 6. 3. (£1.31)

For his effort and Jas. Lloyd, Troedrhiwfer would have received only:

t c q

0 12 0 @ 5/10 per ton = £0.3.6. (17 pence)

t c q

04 10 0 @ 5/10 per ton = £1. 6. 3. (£1.31)

For his effort and Jas. Lloyd, Troedrhiwfer would have received only:

t c q

0 12 0 @ 5/10 per ton = £0.3.6. (17 pence)

Carrying two loads a day from Nant-y-bai to Llandovery, a distance of at least 32 miles would have been more than enough for man and animal along the country roads of those days.

As I mentioned earlier, the Cornishman Joel Williams managed the works on behalf of Lord Cawdor from 1805 to 1823. Later they came into the hands of Messrs. Williams of Redruth, Cornwall and they remained here from 1836 until 1900. Thus there was a Cornish influence at the works during this period, with Cornishmen becoming evident in Pannau Street, Rhandirmwyn in the Census returns of 1841. Among them was John Renowdon who later became publican of the Royal Oak on the village square. Immigrants from Cornwall were still evident in the 1851 Census, with names such as Bargwanan and Morcum appearing in Pannau Street. By 1861 the Cornishmen had almost completely disappeared, possibly giving credence to the local tradition that men from Cornwall had been thrown out of the village after a fierce fight between them and the locals!

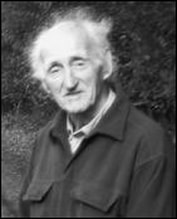

Unfortunately, the lead mining industry was to go the same way as coal in our time, and for the same reasons. Between 1878 and 1885 there was a disastrous fall in the price of lead because of cheap imports from foreign countries. The companies, however, continued to fight on and mined more or less the same quantities until the end of the century. In the 1890’s there was as many as 90 people still employed in the lead mine.

On March 28, 1892 while Captain George Oates was the manager, assisted by Captain Argall, an accident occurred which Lt. Col. R. A. Cundill, the Inspector of Explosives, found it extremely difficult to explain. Two workers, W.J. Beswetherick (aged 25) and J. Lewarne (33) died as a result of an explosion in the mine and the County Coroner, Mr. R. S. Lewis conducted an inquest at the Royal Oak, Rhandirmwyn on April 7, 1892 into their deaths. What probably happened was that Lewarne let down a 50 pound box of gelatine dynamite from the mouth of the 24 fathom level (144Ft.) to Beswetherick who was standing to receive it at the entrance to the 36 fathom level. There was little doubt as to what happened next. While it was being lowered down the shaft the box slipped from its rope and fell free for about 48 feet (15 metres)at most, striking against a wooden platform used to house ladders. Then the explosion occurred, but only part of the contents of the box exploded; most of the contents burned, releasing toxic gasses, which caused the deaths of both men. It was not the explosion, which killed them, since they showed no signs of external injuries other than some superficial scratches. Both men walked home after the accident, but Beswetherick was dead within six hours and Lewarne died two days alter. The mystery to Cundill was that what had caused the explosives to ignite. As he said in his report: ‘But it is not altogether easy to say what caused the explosives to ignite. Numerous experiments have been made with dynamite satisfactorily, neither in experiments nor actual practice have we any record of the simple fall of a case of such explosives, when packed in accordance with the regulations, being ignited or exploded.’

following year the lease was transferred to Nantymwyn Mine Ltd. Who continued to operate the mine with a workforce which varied from 33 to none.

As I mentioned earlier, the Cornishman Joel Williams managed the works on behalf of Lord Cawdor from 1805 to 1823. Later they came into the hands of Messrs. Williams of Redruth, Cornwall and they remained here from 1836 until 1900. Thus there was a Cornish influence at the works during this period, with Cornishmen becoming evident in Pannau Street, Rhandirmwyn in the Census returns of 1841. Among them was John Renowdon who later became publican of the Royal Oak on the village square. Immigrants from Cornwall were still evident in the 1851 Census, with names such as Bargwanan and Morcum appearing in Pannau Street. By 1861 the Cornishmen had almost completely disappeared, possibly giving credence to the local tradition that men from Cornwall had been thrown out of the village after a fierce fight between them and the locals!

Unfortunately, the lead mining industry was to go the same way as coal in our time, and for the same reasons. Between 1878 and 1885 there was a disastrous fall in the price of lead because of cheap imports from foreign countries. The companies, however, continued to fight on and mined more or less the same quantities until the end of the century. In the 1890’s there was as many as 90 people still employed in the lead mine.

On March 28, 1892 while Captain George Oates was the manager, assisted by Captain Argall, an accident occurred which Lt. Col. R. A. Cundill, the Inspector of Explosives, found it extremely difficult to explain. Two workers, W.J. Beswetherick (aged 25) and J. Lewarne (33) died as a result of an explosion in the mine and the County Coroner, Mr. R. S. Lewis conducted an inquest at the Royal Oak, Rhandirmwyn on April 7, 1892 into their deaths. What probably happened was that Lewarne let down a 50 pound box of gelatine dynamite from the mouth of the 24 fathom level (144Ft.) to Beswetherick who was standing to receive it at the entrance to the 36 fathom level. There was little doubt as to what happened next. While it was being lowered down the shaft the box slipped from its rope and fell free for about 48 feet (15 metres)at most, striking against a wooden platform used to house ladders. Then the explosion occurred, but only part of the contents of the box exploded; most of the contents burned, releasing toxic gasses, which caused the deaths of both men. It was not the explosion, which killed them, since they showed no signs of external injuries other than some superficial scratches. Both men walked home after the accident, but Beswetherick was dead within six hours and Lewarne died two days alter. The mystery to Cundill was that what had caused the explosives to ignite. As he said in his report: ‘But it is not altogether easy to say what caused the explosives to ignite. Numerous experiments have been made with dynamite satisfactorily, neither in experiments nor actual practice have we any record of the simple fall of a case of such explosives, when packed in accordance with the regulations, being ignited or exploded.’

following year the lease was transferred to Nantymwyn Mine Ltd. Who continued to operate the mine with a workforce which varied from 33 to none.

Underground workings of all sorts are dangerous places, as the village burial-grounds bear witness, Rhandirmwyn was not an exception. Mr Williams called it a day in 1900 and decided to withdraw from the works.

Even so, not everyone was pessimistic about the future of the works and one who had confidence in the prospects was Mr Octavius Davies of the Old Shop near the village square. Many of the older residents of the village still remember him and his wife well. He and some seven other workers made underground tests between 1908 and 1911. Then in 1914 the lease was acquired by Joseph Argall, who had been a manager at the works in the 1890’s and Argall Avenue in the village was named in his honour.

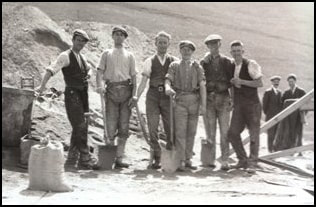

In 1925 the Sulphide Corporation, which was later taken over by Rio Tinto Zinc, showed an interest in the mine. In addition to the lead, this company was interested in the zinc for the purposes of its zinc smelter at Seaton Carew. They had high hopes, since zinc sulphide (sphalerite) is usually found where there is a good supply of galena, and the already extremely effective flotation process offered a better recovery of lead and zinc than the old processes which relied on gravity. A floatation mill which could process 125 tons a day was built and the New Shaft was sunk about 150 yards to the north-east of the Anghred Shaft. 6,615 tons were crushed yielding 165 tons of lead and 529 tons of zinc concentrates. The costs of milling was higher than had been expected, the price of both lead and zinc about £35 a ton, and to crown it all came the serious depression of 1931-2. And as if that were not enough, the situation further deteriorated and a new development proved very disappointing. After clearing the Deep Boat Level in 1931 in the expectation of finding good deposits of zinc sulphide, hardly anything workable was found. In1932 operations were abandoned and the company left the works. So ended a long chapter in the industrial history of the village of Rhandirmwyn.

Dafydd Dafis.

Published 1993

Even so, not everyone was pessimistic about the future of the works and one who had confidence in the prospects was Mr Octavius Davies of the Old Shop near the village square. Many of the older residents of the village still remember him and his wife well. He and some seven other workers made underground tests between 1908 and 1911. Then in 1914 the lease was acquired by Joseph Argall, who had been a manager at the works in the 1890’s and Argall Avenue in the village was named in his honour.

In 1925 the Sulphide Corporation, which was later taken over by Rio Tinto Zinc, showed an interest in the mine. In addition to the lead, this company was interested in the zinc for the purposes of its zinc smelter at Seaton Carew. They had high hopes, since zinc sulphide (sphalerite) is usually found where there is a good supply of galena, and the already extremely effective flotation process offered a better recovery of lead and zinc than the old processes which relied on gravity. A floatation mill which could process 125 tons a day was built and the New Shaft was sunk about 150 yards to the north-east of the Anghred Shaft. 6,615 tons were crushed yielding 165 tons of lead and 529 tons of zinc concentrates. The costs of milling was higher than had been expected, the price of both lead and zinc about £35 a ton, and to crown it all came the serious depression of 1931-2. And as if that were not enough, the situation further deteriorated and a new development proved very disappointing. After clearing the Deep Boat Level in 1931 in the expectation of finding good deposits of zinc sulphide, hardly anything workable was found. In1932 operations were abandoned and the company left the works. So ended a long chapter in the industrial history of the village of Rhandirmwyn.

Dafydd Dafis.

Published 1993

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Mrs Mary L. Jones, Mr Handel Jones and Mr Rod Walters the three from the village of Rhandirmwyn. Mr David Owen, Newport; the Staff at the National Library of Wales, especially Dr. W. Brian, L. Evans, Carmarthenshire Archivist; the late Capt. H.R.H. Vaughan, Nantymwyn.

RESEARCH DOCUMENTS

G. W. Hall, Metal Mines of Southern Wales.

John E. Lloyd., A History of Carmarthenshire.

Mrs Mary L. Jones, Mr Handel Jones and Mr Rod Walters the three from the village of Rhandirmwyn. Mr David Owen, Newport; the Staff at the National Library of Wales, especially Dr. W. Brian, L. Evans, Carmarthenshire Archivist; the late Capt. H.R.H. Vaughan, Nantymwyn.

RESEARCH DOCUMENTS

G. W. Hall, Metal Mines of Southern Wales.

John E. Lloyd., A History of Carmarthenshire.